Former ADOC Lieutenant gets 7 years in prison. Some say he got away with murder.

Despite record of misconduct, ADOC promoted Mohammad Jenkins through the ranks until 2022, when a man he assaulted died a week later.

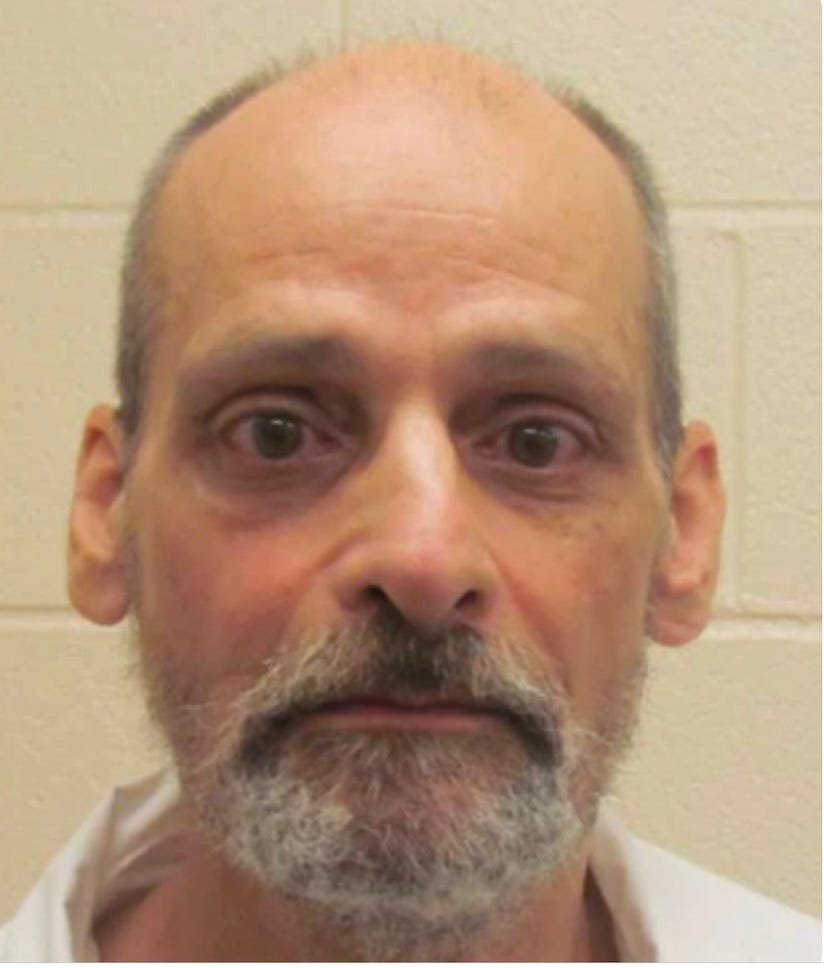

(Mohammad Jenkins outside a Bessemer courtroom in April of 2022.)

The last time Victor Russo spoke to his mother, he told her that he loved her. He called her on a prison tablet from a segregation cell at the William E. Donaldson maximum-security prison in Bessemer on February 23, 2022.

48 hours later, Russo died at UAB Hospital from an inoperable brain bleed caused by blunt force injuries to his head.

The prison claimed Russo’s fatal injury was sustained in a fall and not the prolonged beating by Lt. Mohammad Jenkins that was caught on a prison surveillance camera a week prior. The medical examiner agreed and classified Russo’s death as an accident.

So Jenkins was charged with assault, not murder. The fact that he was charged at all is amazing and likely only thanks to Russo’s final letter which listed the specific prison cameras that captured the assault.

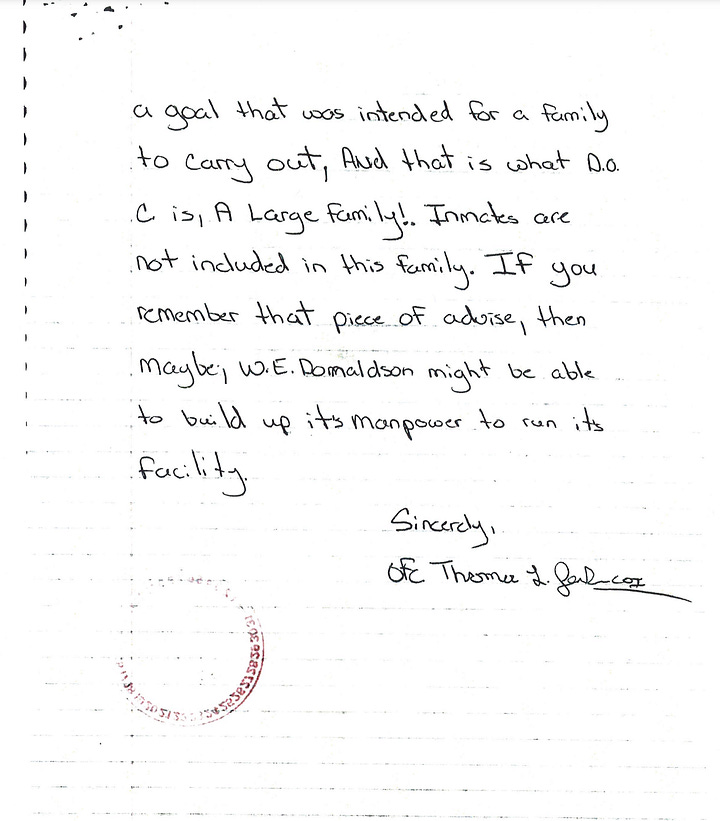

(Victor Russo with two nieces during a prison visit around 1999. Photo provided by Patricia Russo.)

The saga surrounding Russo’s death and Jenkins’ prosecution is the final chapter in a long, horrifying story about an officer in an out-of-control prison system, who preyed on incarcerated men, using violence and cruelty with abandon.

But it’s also part of a larger pattern: for 20 plus years, ADOC promoted Mohammad Jenkins through the ranks, while he left behind a long paper trail of problematic behavior. His career with ADOC provides a case study into an agency that may declare publicly it has zero tolerance for excessive force, but quietly rewards it.

This case also demonstrates the limited impact of the U.S. Department of Justice, which sued the state in 2020 after concluding that ADOC violates the Constitution due to pervasive violence and excessive force by prison staff.

But despite all the firepower of the federal government, preventable deaths like Russo’s continue to occur inside Alabama prisons at a record pace, right under the DOJ’s nose, with no end in sight.

THE SENTENCING

December 19, 2023. Mohammad Jenkins entered the courtroom from a side door, flanked by two scowling U.S. Marshals. Jenkins, handcuffed and wearing an orange Shelby County jail jumpsuit, smiled broadly at his family members in court, then sat down at the table with two attorneys from the Federal Public Defenders office.

I sat in the courtroom scribbling notes. This was the second time I’d seen Jenkins in person. The first time was April of 2022 when he appeared before a Bessemer judge to face state charges of assault stemming from the same incident.

For years, I’d heard about Jenkins from sources inside Donaldson prison. They dreaded his presence and feared his wrath. Jenkins didn’t just abuse men in prison, they told me, he bullied and humiliated them.

Jenkins, 52, is a huge man. Over 6 feet tall, 280 pounds.

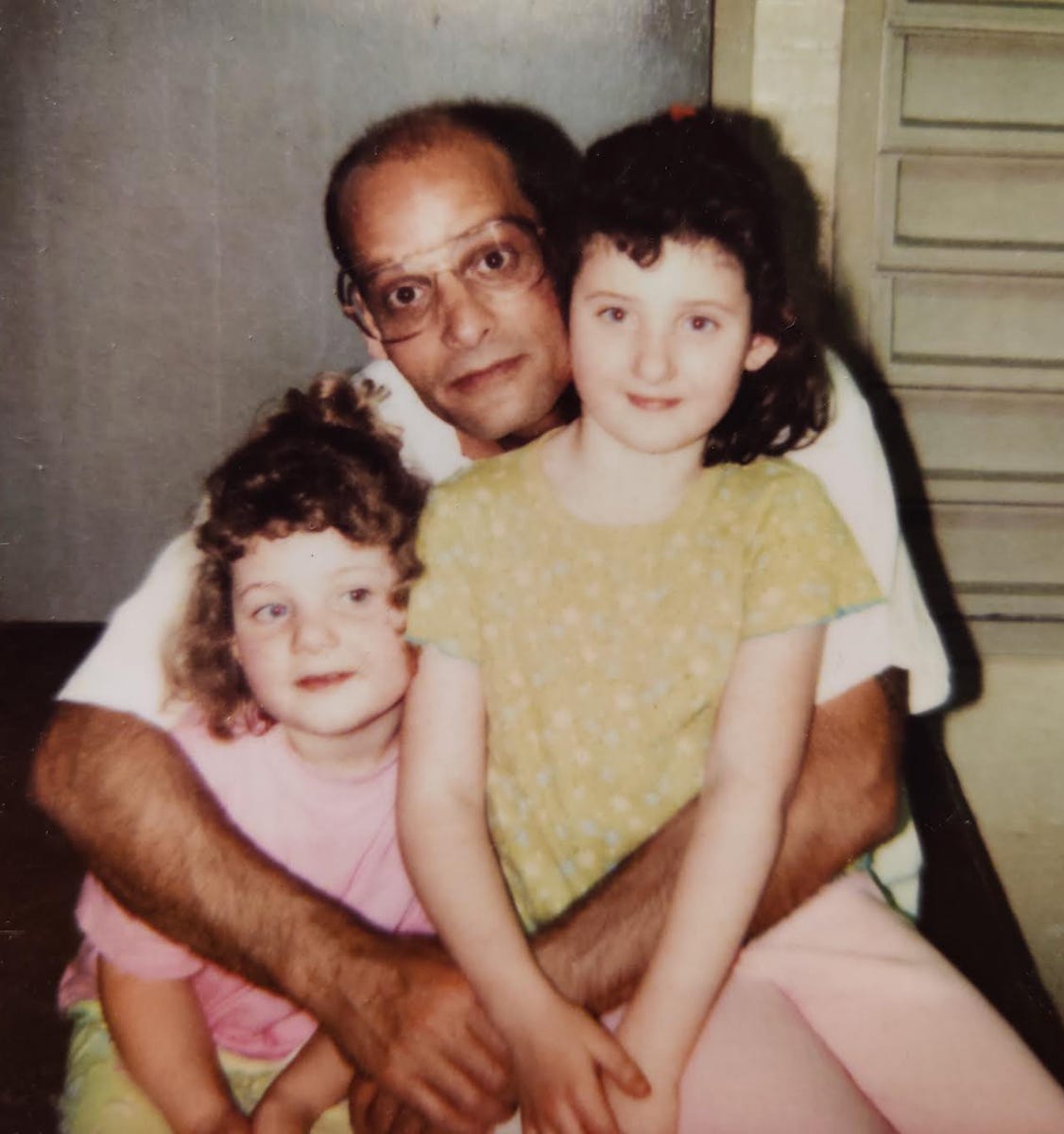

When he beat Victor Russo on February 16, 2022, Russo stood at just 5 feet 10 inches, 162 pounds.

By all accounts, Russo was a harmless man who had grown feeble during his decades of incarceration, who appeared much older than his 60 years. He could be cranky, but never violent. Certainly no match for the brute force of Jenkins.

(Victor Russo’s most recent ADOC photo.)

In the federal courtroom on December 19th, we gathered to hear Jenkins’ punishment. He had already pleaded guilty to assaulting Russo and another handcuffed man at Donaldson prison, and lying to cover it up.

Federal sentencing guidelines carried a range between 87 and 108 months. Jenkins’ attorneys asked Chief Judge L. Scott Coogler for a reduced sentence of 61 months. They pointed to his military service, and a recent diagnosis of PTSD, while prosecutors emphasized the brutality of the assault.

(The federal courthouse in Birmingham where Jenkins was sentenced on December 19, 2023.)

Jenkins admitted to kicking, punching, and slapping Russo after he’d handcuffed Russo’s right arm to a bench in a holding cell. Jenkins also sprayed Russo with chemical spray, at one point putting the nozzle directly into Russo’s mouth, then striking him on the head with the can and hitting him in the face with Russo’s own shoe.

During the hearing, prosecutors played segments of the soundless surveillance video showing the assault. We watched Jenkins slam Russo to the floor of the prison gym, then drag him by his clothes to a holding cell, and cuff him to a bench. Russo, appearing thin and frail, tried to protect his head with flailing arms. At one point, he crouched in a ball, hands over his head.

For five minutes, Jenkins took breaks from the beating and sat on a table facing Russo’s cell, then repeatedly went back in and beat Russo some more. The video later cut to Russo in the prison infirmary with Jenkins appearing to shout in his face as nurses stood nearby. Jenkins paced the floor as nurses looked Russo over. At one point Jenkins pushed Russo’s shoulder, then put his hands on Russo’s face. Russo swatted him away.

Jenkins’ mother asked the judge for leniency and said her son had never given her any trouble. A sister also spoke and called Jenkins her superhero. She described a man who pulled himself up by the bootstraps to work as a nurse and a law enforcement officer. Another sister talked about her own experience with PTSD from military service and said her brother had always been the type to hold everything in.

Then Jenkins leaned forward to speak into a microphone on the defense table, addressing the court in a composed, soft-spoken voice.

“I’d just like to say, I take full responsibility for my actions. I always wanted to be the best that I could be. That’s why I became a nurse, went into the Marine Corps, became a police officer and became a corrections officer. I just felt an overbearing pressure to protect and that’s what led me to my situation now. I just really am ashamed of my actions that got me here. I really would have loved to be before you as a lawyer. I hate that I put this on everybody in my family. I cry every night in my cell……”

Jenkins shook his head as he tried to compose himself. During a long pause, members of his family murmured encouragement from their seats in the courtroom. A clerk brought Jenkins a box of tissue. He continued, his voice shaky.

“I’m not supposed to be here. This is not supposed to be going on. It’s like a nightmare. I just apologize to the court, to my family. I’m just sorry, judge. I’m sorry.”

A federal prosecutor pointed out that Jenkins neglected to apologize to the two victims that he admitted to assaulting. The prosecutor called Jenkins a bully who took advantage of vulnerable people.

“He abused his authority as a corrections officer,” he said. “Not only an officer, but he was a Lieutenant and a shift supervisor who was responsible for the entire shift when he was working,” he added. “He was obviously setting a poor example for his subordinates.”

Before Judge Coogler announced his decision, he asked whether there was any indication that Russo died as a result of injuries from the assault by Jenkins. A prosecutor said they were not able to prove this, “due to a hastily performed autopsy.” Judge Coogler mused aloud that Russo seemed to be walking fine after the beating.

“I have seen far worse assaults in prison by prison guards,” Coogler said. “Yours just happened to be caught on video.”

Coogler also said he believed Jenkins suffered from PTSD and had anger issues, but his conduct wasn’t justified.

“We as society have to depend on men and women that work in such facilities to uphold standards of humanity,” Coogler said. “They have a job to protect those in the prison. This wasn’t a case of him defending himself.”

In the end, Coogler sentenced Jenkins to 87 months in prison, just over seven years. He assured Jenkins that he’d be out before he knew it.

“I could have loaded you up and given you a lot of time,” Coogler said, “but I frankly didn’t believe that would be appropriate, considering your military service, considering all the things you have done right.”

The U.S. Marshals quickly ushered Jenkins out of the courtroom and I went home to call Victor Russo’s mother with the news.

Rosemary Collins is 85-years old. I’ve spoken to her many times over the years. For a long time, she was part of a group of mothers of incarcerated men who lobbied Alabama’s legislature to improve the abysmal conditions their sons endured.

Her voice sounded tired on the phone. I told her Jenkins would serve just over seven years in federal prison.

“Ok.,” she said. Then she told me she forgave him.

“You have to forgive people,” she explained. “I forgave him so I can live with myself. I can’t carry that grudge. It’s not good for you.”

I asked her what she would want people to know about her son. She started to cry.

“I know that he matured in prison. I hate that he had to go to prison to mature, but he became a very intelligent person, a good person.”

She apologized for crying. I told her it was OK.

She told me that Victor got to know God during his incarceration, and became active in his faith.

“It’s a beautiful thing,” she said between sobs. “I’m proud of him. He turned his life around.”

We sat in silence for a moment before she spoke again.

“And I know he’s now at peace,” she said. “I’m glad he’s out of that place.”

THE ASSAULT

February 16, 2022. Mohammad Jenkins’s began his assault on Victor Russo while Russo was on his way to the prison’s “chow hall” to eat breakfast. Jenkins stopped him and said the chow hall was closed. Russo stood and stared at him, then Jenkins put his hand on Russo’s head, Russo threw his hands up to keep his balance and Jenkins, claiming Russo hit him, sprayed Russo with chemical spray.

These details about how the incident began are from a letter dated February 22nd, that Russo wrote three days before he died. His mother, Rosemary, received a copy of the letter on February 24th, the same day she was summoned to UAB hospital to see her son for the last time. By then Victor Russo was brain dead.

He died the following day, on February 25th, just after 2am. I first learned of his death from the Jefferson County medical examiner. Their office sends out a daily email that lists new death investigations. I began subscribing just to stay informed of the death toll at Donaldson prison.

266 people died inside ADOC in 2022, the highest number of prison deaths in state history. According to Equal Justice Initiative, nearly a third of those deaths were due to homicide, suicide or overdose.

On the morning of February 25th, 2022, I opened the email from Jefferson County’s Medical Examiner and said “Oh shit” when I saw Victor’s name. I knew Victor—I’d spoken to him on the phone about some of his experiences in prison, and written about several horrific assaults he’d survived during his last decade in prison. Russo had been in prison since 1987, serving a life sentence for a drug-related murder.

Shortly after learning of his death, I began hearing from sources inside the prison about what happened. One man told me he heard Lt. Jenkins had beaten Russo to death. Then another said the same thing.

I emailed ADOC’s public information office asking for details about his death. They ignored my request, but did respond to reporter Eddie Burkhalter, who forwarded their statement to me.

In an email to Burkhalter on the afternoon of February 25th, ADOC said foul play was not suspected in Russo’s death and the agency was not investigating the death as a homicide. But there was a big problem with that story. Russo’s letter detailing the assault by Jenkins had made it out of the prison before he died. In the letter, Russo cited numerous prison cameras that could verify his account.

Russo’s letter provides a vivid first person account of what he endured on February 16th, 2022. He wrote that after Jenkins doused him with chemical spray, he dropped to the floor, but Jenkins yanked him up and marched him to the prison’s East hall gym, intermittently hitting Russo in the head with the spray can and spraying him in the face with more chemicals.

“As we went by the shift office, I saw four officers sitting in there looking at me getting beat,” Russo wrote.

Once Jenkins got Russo into the gym, he dragged him into a holding cell, hit him with his fist, then handcuffed him to a bench, according to Russo’s letter.

(Mohammad Jenkins outside a Bessemer courtroom in April of 2022.)

What Russo wrote about the rest of the assault matches what appeared to occur in the surveillance video that was played in court.

“He cuffed me to the bench and beat me some more and maced me,” Russo wrote. “He even stuck the nozzle of the mace can in my mouth and pulled the trigger.”

Jenkins went to the center of the gym, then came back and beat Russo again. When Lt. Jenkins finally left, Russo wrote that he sat cuffed to the bench in the holding cell for 15 minutes, until another officer showed up and took him to the prison infirmary, where Russo encountered Jenkins again.

“Lt. Jenkins walked up behind me…. stuck his finger in my face and said this is where you bit me. His finger was about an inch from my nose. He did this several times like a big kid,” Russo wrote.

(An earlier ADOC photo of Victor Russo.)

Then, according to Russo’s letter, Jenkins brought him to cell D-45, where he would stay until he was rushed to UAB hospital on February 23rd.

“Jenkins said that if I said anything to anybody, he would keep (me) in lockup,” Russo wrote.

If all this wasn’t enough, officers did not allow Russo to shower until the following day, even though he was soaked in chemical spray.

“I had been maced from head to toe,” he wrote. “My cellmate was gagging all night.”

Russo’s letter concludes by describing a disciplinary hearing officers held on February 18th, in which Lt. Jenkins charged Russo with three major infractions, including assault on an officer and possession of a knife, which Russo vigorously denied.

Despite his sentence of life without parole, Russo was still hopeful that he could one day get out of prison and he did not want his record tarnished with bogus charges.

“If you shake down the Lt. office on the west hall,” Russo wrote, “you’ll find all kinds of knives that people (inmates) turn in to get favors. Therefore, he would have a knife to plant on me. You might find cell phones and drugs in there also.”

Russo closed the letter by addressing the warden directly.

“Ms. Morgan, I did not do what Lt. Jenkins is claiming. I never own a knife since 1989. I’ve had to learn to take myself out of situations through talking.”

A month after Russo died, ADOC reversed its previous statement, something that rarely ever happens. After stating on the record that no foul play was suspected in Russo’s death, the agency announced that Jenkins was under arrest for assaulting Russo and had resigned from ADOC.

ADOC said Jenkins was arrested after their investigation “produced sufficient evidence that excessive force was used by Jenkins against Russo,” but that Russo’s exact cause of death was still pending results of his autopsy.

“The ADOC’s LESD, the FBI’s Northern District Office, and the Jefferson County Coroner’s Office will continue to work collaboratively to complete a comprehensive investigation,” the agency stated.

I obtained a copy of Russo’s autopsy report, which details numerous blunt force injuries to Russo’s chest and extremities, but the fatal injury is identified as a “right subdural hematoma” caused by a contusion on the right side of his forehead.

A right subdural hematoma is defined as a “serious condition where blood collects between the skull and the surface of the brain.” The associate medical examiner attributed the cause to “blunt force injuries of head most likely sustained in a fall,” and declared the manner of Russo’s death an accident, and not a homicide.

The medical examiner wrote that the fatal head injury was “only one or two days old” and “the bleeding around the brain did not occur during the assault on February 16th. Based on the location of the impact site on Mr. Russo’s head, the injury was most likely sustained in a fall that occurred sometime on the 23rd. More simply stated, Mr. Russo was assaulted; however, the injuries from the assault did not cause or directly contribute to his death.”

What is the source of information about Russo suffering a fall inside the prison?ADOC’s initial statement said Russo died after his cellmate “reported Russo had passed out,” but the agency never mentioned Russo being injured in a fall, in any of its statements about the case.

A short narrative report by a deputy coroner on the day of Russo’s death also doesn’t mention anything about a fall. The deputy coroner wrote that someone from UAB called the medical examiner’s office to report Russo’s death, that he’d been an inmate at Donaldson prison and arrived at UAB’s emergency room on February 23rd after he was found in his cell and “he appeared to be the victim of an assault.”

The deputy coroner also wrote that he spoke with ADOC agent Clark Hopper who “will forward all reports prepared by prison officials to me next week.” I hoped to view these additional documents that the medical examiner no doubt used to reach his conclusion, but because they were produced by ADOC, the medical examiner’s office said they were not authorized to release them.

THE CELLMATE

I tracked down the man who was in cell D-45 with Russo and we spoke by phone. McArthur Lynch disputed the account that Victor suffered a fall before his death. He told me he believes Lt. Jenkins killed Russo in a subsequent assault that occurred after the original February 16th incident.

Lynch said after the first assault, Jenkins brought Russo to the cell with a black eye and scratched up knees, covered in chemical spray. He said he helped Russo write the letter that he sent to his mother and allowed Russo to use his tablet to call his mother.

Sometime after that, the timeline is unclear, Lynch said Lt. Jenkins came back to their cell and took Russo out, saying they needed to take pictures of his injuries. When Russo returned, Lynch said Russo told him that Lt. Jenkins had hit him in the head again.

“He said, ‘he keeps messing with me,’” Lynch said. “He was scared to take a shower and stuff.”

Lynch said on the night of February 23rd, he’d been listening to music on his tablet, but came down off his bunk and saw that Russo appeared to be having a seizure in his bed. Lynch banged on their cell door and called for help and eventually officers carried Russo out of the cell.

(Victor Russo before prison in the Army National Guard.)

Lynch said he told the wardens, and investigators with the FBI and ADOC the same thing, that he believed Jenkins was responsible for Russo’s death.

For a few days after Russo died, Lynch said he was investigated as a possible suspect in the death. He said Jenkins came to his cell during that time and pressured him to sign a report stating that Russo bumped his head in a fall.

“He said ‘that’ll cover you and cover us too,’” Lynch said.

Lynch refused to do it and said he was scared afterward that Jenkins would come after him. Late last year, Lynch was transferred to a different prison. He gave me permission to use his name in this story, because he gave Russo his word that he would tell people what happened to him.

“A lot of things they try to cover up,” he said. “The only witness Russo had is me and the letter he wrote. The man shouldn’t have gotten killed. It traumatized me a lot.”

THE RECORD

Mohammad Jenkins worked in law enforcement for over 20 years and the beating of Victor Russo was hardly an isolated incident. Since 2005, men incarcerated in ADOC have filed at least 16 federal lawsuits alleging excessive force and abuse by Jenkins.

The allegations are consistently harrowing—dragging a handcuffed man into a corridor, opening his legs and beating his genitals, causing permanent injury. Standing on another man’s neck, smashing yet another man’s head into the glass window of a prison cubicle.

In 2005, a lawsuit filed by the mother of a mentally ill man named Charles Agee alleged that a group of officers, including Jenkins, sprayed Agee with chemical spray and then beat Agee with batons, cuffed him, put his feet in restraints, and took him to the infirmary.

There, another officer shoved Agee violently into a chair and Agee’s head struck a concrete wall. He was knocked unconscious, then began vomiting and having a seizure. He died a short time later.

The autopsy revealed abrasions, contusions, lacerations, and four broken ribs, which punctured his lung and lacerated his spleen, causing Agee to bleed to death. The coroner ruled his death a homicide, but no one was criminally charged. In 2009, ADOC settled a wrongful death lawsuit with Agee’s mother for an undisclosed amount of money.

A sentencing memorandum filed by Jenkins’ attorneys included some biographical detail, a background marked by poverty and violence, striking in its similarity to that of so many people in prison.

According to the memo, Jenkins grew up in government housing where he was “punched and slapped by his stepfather on a regular basis.”

When Jenkins was just 12-years old, both his father and stepfather were murdered. His older brother was born with cerebral palsy and Jenkins helped provide the 24-hour care his brother required.

Jenkins graduated from Birmingham’s Jackson-Olin High School in 1989 and immediately joined the Marines, which “provided an opportunity to serve his country, escape poverty, learn to protect himself, build self-esteem and escape inner-city Birmingham.”

Jenkins saw the Marines and law enforcement as a chance to serve and protect. “He never intended to become the person that brings him before this Court for sentencing,” the memo states.

After he left the Marine Corps in 1993, he attended community college. Beginning in the late 1990s, Jenkins served in several law enforcement positions, including as correctional officer at the Birmingham jail, and a police officer in the small cities of Brighton and Kimberly. He also worked as a security officer around children with the Department of Youth Services of Alabama.

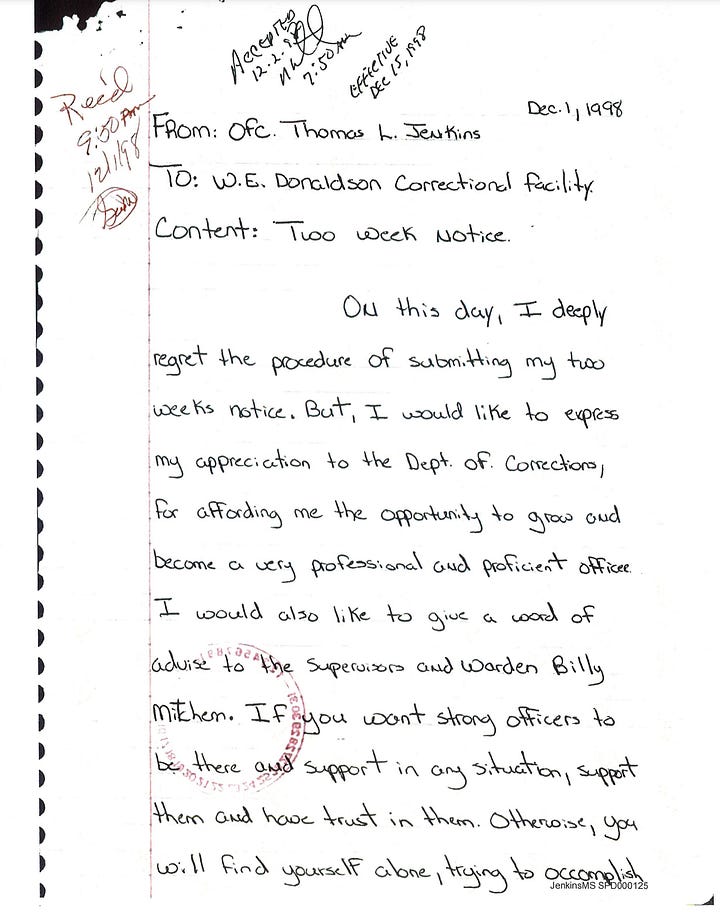

Jenkins first worked as a correctional officer at Donaldson prison for 17 months in 1997-1998, but left due to “lack of employee security due to staff shortages,” according to resignation paperwork in his state personnel file.

He wrote a resignation letter that included advice to the prison warden. “If you want strong officers to be there and support in any situation, support them and have trust in them,” Jenkins wrote. “Otherwise, you will find yourself alone, trying to accomplish a goal that was intended for a family to carry out, and that is what DOC is, a large family! Inmates are not included in this family.”

Jenkins returned to work for ADOC in 2004 where he stayed until 2022. I obtained his personnel file that shows a wildly inconsistent record as an employee. During those 18 years, Jenkins received at least seven written reprimands for insubordination, disagreeable behavior, violating rules, using abusive language and failing to perform his job properly.

In 2006, ADOC removed Jenkins from the Corrections Emergency Response Team, also known as “CERT,” due to several incidents in which incarcerated men complained that Jenkins had assaulted them.

According to a memo in Jenkins’ file, the assaults occurred when the CERT teams entered Donaldson prison for “familiarization.” ADOC investigated the complaints and the officer in charge of CERT agreed that Jenkins needed to be removed due to his “mannerisms, which is not in the best interest of the DOC.”

ADOC also suspended Jenkins for major misconduct at least four times during his career. In 2009 he was suspended for 10 days without pay for “disgraceful conduct” after pleading guilty to forging a military document.

A letter from ADOC’s commissioner states that Jenkins was charged in a domestic violence case in 2007, but he told the judge he couldn’t make a court date because he was being deployed to Iraq. He produced a military document to validate this, but Homewood police determined it was forged. Jenkins pleaded guilty to possession of a forged instrument, a misdemeanor, and served 2 years on probation.

In 2011, he received two written reprimands for unsatisfactory cooperation with coworkers and disagreeable behavior, but then in 2012, ADOC promoted him to Sergeant and gave him a raise.

Two years later in 2014, Jenkins was suspended for three days without pay after getting into a fight with another officer while conducting an unauthorized training exercise.

"You and the officer became overly aggressive and a physical altercation occurred that resulted in your pants being torn from your knee to your hip,” ADOC Commissioner Kim Thomas wrote in Jenkins’ suspension letter. “The officer's uniform shirt and undershirt were torn and he sustained an injury to his head."

That same year, Jenkins pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor domestic violence charge of harassing communications. The warrant states that Jenkins sent several threatening text messages and a sexual video to a woman’s phone. Two years later, ADOC once again promoted Jenkins, this time to the position of Lieutenant, and gave him another raise.

In the three years following Jenkins promotion to Lieutenant, Jenkins received multiple reprimands for violating rules, using abusive language and failing to perform his job properly. Then in 2019, he was suspended twice without pay.

In May of 2019, ADOC suspended Jenkins for two days after he failed to assign an officer to the youthful offender dorm for an entire weekend. Reports indicated the young men in the dorm missed entire meals and were left totally unsupervised.

Then in September of 2019, ADOC suspended Jenkins for three days after he used abusive language with prison staff. The record states that Jenkins called another officer “a dumb ass nigger” and then denied it.

One longtime source told me about a 2020 incident at Donaldson in which he witnessed Jenkins bodyslam a man onto the pavement and then drape his unconscious body on a laundry cart, yanking his pants and underwear down to his ankles to expose his butt.

I asked my source why Jenkins would do such a thing.

“To humiliate him,” he replied. “I’m actually surprised the guy survived.”

(Mohammad Jenkins leaving a Bessemer courtroom in April of 2022.)

In 2021, ADOC suspended Jenkins for two days without pay for once again, fighting with a fellow officer.

The sentencing memo submitted to the court offers some context about problems in Jenkins personal life that likely contributed to his terrible behavior. Jenkins’ attorneys wrote that he suffered from undiagnosed PTSD, insomnia and suicidal ideation connected to his military service and like so many veterans, he self-medicated with alcohol.

His attorneys argued that Jenkins’ PTSD was aggravated by the unsafe environment inside ADOC and Jenkins was afraid of losing his job if he asked for help. The sentencing memo called the indictment against Jenkins “an awakening for him to seek help for his mental health.”

In 2023, Jenkins sought treatment at the Birmingham VA, stopped drinking and began taking medication for depression.

In the midst of Jenkins’ fraught final years at ADOC, the DOJ determined in 2020 that men incarcerated in ADOC “are subjected to excessive force at the hands of prison staff.”

In a 30-page findings letter to Governor Ivey, the DOJ found that correctional officers’ frequent “use of batons, chemical spray, and physical altercations such as kicking—often result in serious injuries and sometimes death.”

But those words weren’t enough to stop Jenkins from assaulting Victor Russo two years later.

Jenkins was the subject of another investigation, and although he wasn’t criminally charged, a federal court awarded $1000 in damages to the incarcerated man injured in the incident, after a bench trial in 2022. The court found that Jenkins dragged a mentally ill man from his cell, then “slammed him to the ground, and punched and slapped him after deploying a chemical spray called ‘Cell Buster’ to restrain him.”

U.S. District Judge Abdul K. Kallon wrote that he found the incarcerated men who testified against Jenkins credible and specific, but just the opposite with Jenkins.

“In contrast, Jenkins was hostile and combative to simple questions on cross examination and became angry, making it easy to believe him capable of the conduct at issue," the judge wrote. He concluded his order with an unusually frank pronouncement about prison violence.

"Indeed, it is perhaps within the cell blocks of prisons and jails that one’s constitutional rights are most in jeopardy and, thus, in need of safeguarding from the likes of Jenkins."

When ADOC announced Jenkins’ arrest in Russo’s assault, it included an expected statement condemning prison abuse.

“The ADOC condemns all violence in its facilities, and use of excessive force by ADOC staff is not tolerated.”

But Jenkins’ record proves otherwise. It was only within the walls of this system that this violence occurred and in Jenkins case, was repeatedly rewarded with promotions and raises.

Until our society figures out a way to hold the entire system accountable, and not just a few bad actors, until we rethink the corrupting nature of absolute power, state violence and preventable deaths will continue to happen on our dime.

And men like Victor Russo will continue to lose their lives.

Very comprehensive, unlike most news items I read, thanks.

Great journalism. Takes pieces like this to have any hope at all of reforming the system. The truth is lucky to have you in its corner. Thank you.