Casey Daniel Cook was looking forward to coming home from prison. The 26-year old father was scheduled to be released from Bullock Correctional Facility on September 9th and had a job lined up as a brick mason apprentice. This was Cook’s second time in prison for drug-related crimes and family members said he’d completed a prison drug program and was determined to turn his life around. He called his “Nanny,” Linda Golden, every day from prison, sometimes twice a day.

In one of the last conversations they had, he promised Golden that he’d never come back to prison.

“He told me, ‘I just want to come home and live a normal life,’ Golden said. “He said, ‘I want to prove to everybody that I’m not just a piece of trash.’ And I said, Buddy, you will.”

Instead, Casey Cook died in his prison bed on July 26, with only six weeks left to go on a one-year sentence. Golden said she spoke to Bullock’s warden, Patrice Jones, who told her Casey’s death appeared to be an overdose, but gave her no other information. Golden asked Jones about an autopsy report and said Jones told her the prison doesn’t receive autopsy reports. She asked Jones who she could call about it and Jones replied that she didn’t have a number.

“It’s strange to me that she wouldn’t want to know how one of the prisoners died,” Golden said. “I mean, is this woman lying to me? Don’t they get a report? Don’t they have to make a report about what happened?”

(Casey Cook and Linda Golden)

When Casey Cook died on July 26, he became the 8th suspected drug-related death inside Alabama prisons during the month of July. In the 5 days that followed, three more men would die inside three other prisons, bringing the monthly death toll connected to contraband drugs to an all time high of 11 people. And the deaths keep coming, as reported by The Montgomery Advertiser in yet another story about a family reeling from the sudden death of their loved one on August 9th at Bibb Correctional Facility.

So far this year, 27 people have died in ADOC from suspected overdoses, by far the highest number since 2018, when I began tracking deaths inside Alabama prisons. By comparison, I tracked 22 suspected drug-related deaths in all of 2021 with 13 confirmed drug-related through autopsy reports. I’m still waiting to receive requested autopsies on the other nine, but at the time of death, sources told me that drugs were suspected as the cause.

While leaders like Gov. Kay Ivey and Attorney General Steve Marshall remain silent on this catastrophe, Casey Cook’s family and dozens of others try to cope with the sudden and unexplained loss of their loved one inside Alabama prisons.

“This has been horrible,” said Joseph Gallahar, Cook’s stepfather. “It breaks my heart. He should have been able to serve his time away from all that stuff that he was trying to put behind him. And if he did overdose on drugs, how did he get them? The whole thing is just corrupt, from the guards on up.”

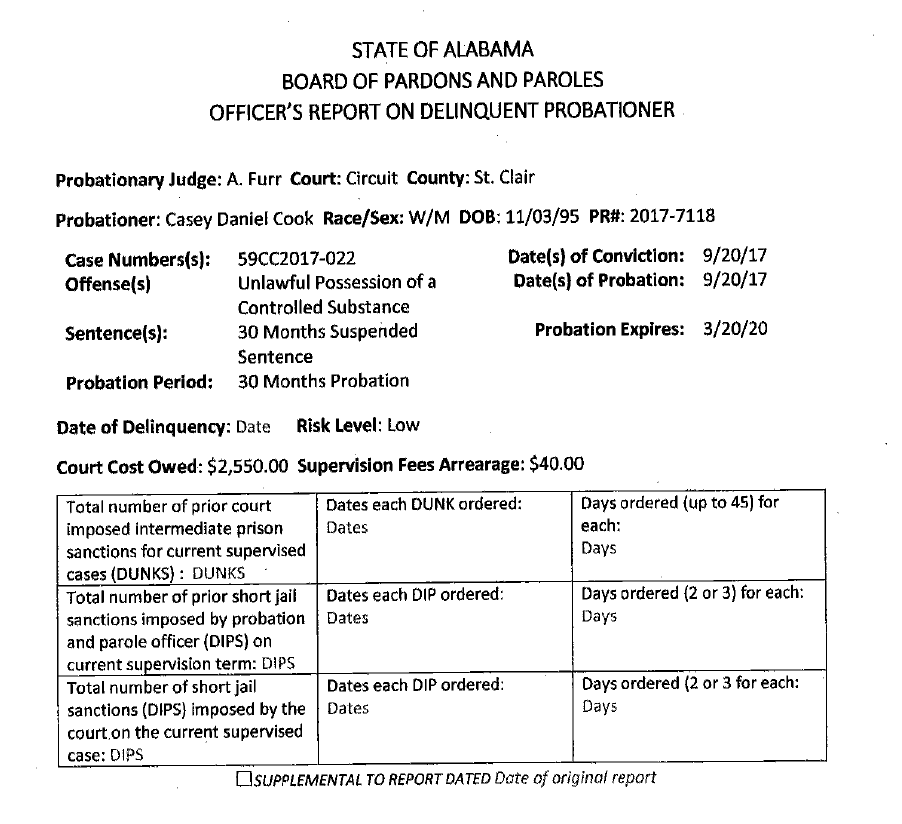

Casey Cook’s short criminal record and sudden death provide a case study in why incarceration, especially in Alabama’s drug-filled prisons, is a terrible solution to crimes that are directly related to substance use and addiction. Cook pleaded guilty in September of 2021 to drug possession and agreed to serve a year in prison. The complaint shows he was arrested in July, 2021 in St. Clair County with GHB or “liquid ecstasy,” a party drug sometimes linked to blackouts when mixed with alcohol.

The reason Cook agreed to prison time is likely because this wasn’t his first time to get in trouble. In 2020 he walked away from work release in Childersburg, was arrested a day later and pleaded guilty to second degree escape. In 2018 he pleaded guilty to receiving stolen property while he was already finishing a sentence for 2017 drug possession and third-degree burglary convictions.

The 2017 drug possession complaint shows he was caught with meth, 5 oxycodone pills and 2 xanax pills. Family members say he’d been experimenting with drugs since graduating high school in 2014.

“He used everything, to be honest about it,” said Golden, including an emerging street drug called “water” that consists of a joint dipped in PCP.

Looking through Cook’s court records, it appears that prosecutors and a judge in St. Clair County gave him a chance to serve probation for the 2017 cases, but he missed a meeting with his probation officer and later a court date. He’d been attending drug treatment, but was obviously relapsing. So what did the system do? A judge revoked Cook’s probation and remanded him to prison.

I couldn’t help but notice the language in Cook’s revocation documents—”absconding is a high level violation” and “he will continue to have compliance issues.” It makes it sound like Cook was simply an out-of-control, incorrigible danger and not someone who just needed help. We know people struggling with substance use or addiction can relapse multiple times during recovery, yet the courts seem to have their finger on the trigger, ready to terminate prison diversion the minute someone screws up. What if instead of sending Cook to prison, the probation officer recommended in-patient treatment? Is that ever recommended? Is it even an option in Alabama? I’m not sure, but I doubt it.

This approach makes zero sense when everyone knows Alabama prisons operate like an open-air drug market. Dope is everywhere, dope sick people are everywhere, dope traffickers are everywhere. And now, one more young life is gone. A person who still had a chance to succeed was sent into a hopeless environment flooded with drugs. And that person didn’t just relapse, he died. Our system is setting people up to not only fail, but to perish, to be completely erased.

It doesn’t help that the media reinforces harmful narratives that people like Casey are irredeemable or stupid. This headline from The Anniston Star surprised me with its callous tone, but it’s too easy for reporters to pile on when someone like Casey messes up. In this story, Casey is not a man, he’s reduced to a “jail inmate” who “keeps getting caught.” The lens this story looks through is clearly that of law enforcement.

I worked in local media for 20 years and the connotations with many news stories about crime are gross—that people are monsters or losers or freaks. It’s a big reason I now work as an independent journalist. That slant is not truthful and I no longer wanted to be a part of the harm machine. That doesn’t change the reality that I made a living for two decades off the commodification of human misery, but I sleep better at night now, saying and writing and reporting something closer to the truth.

Casey Cook’s life was one marked by incredible loss. His mother and baby brother were killed in a car accident when Casey was 7-years old. For the rest of childhood and adolescence, he drifted between living with his remaining family, including his stepfather, Joseph Gallahar, and Linda Golden, who is technically a great aunt but filled the role of grandmother for Casey. “I’m the only nanny that Casey has ever known,” she told me.

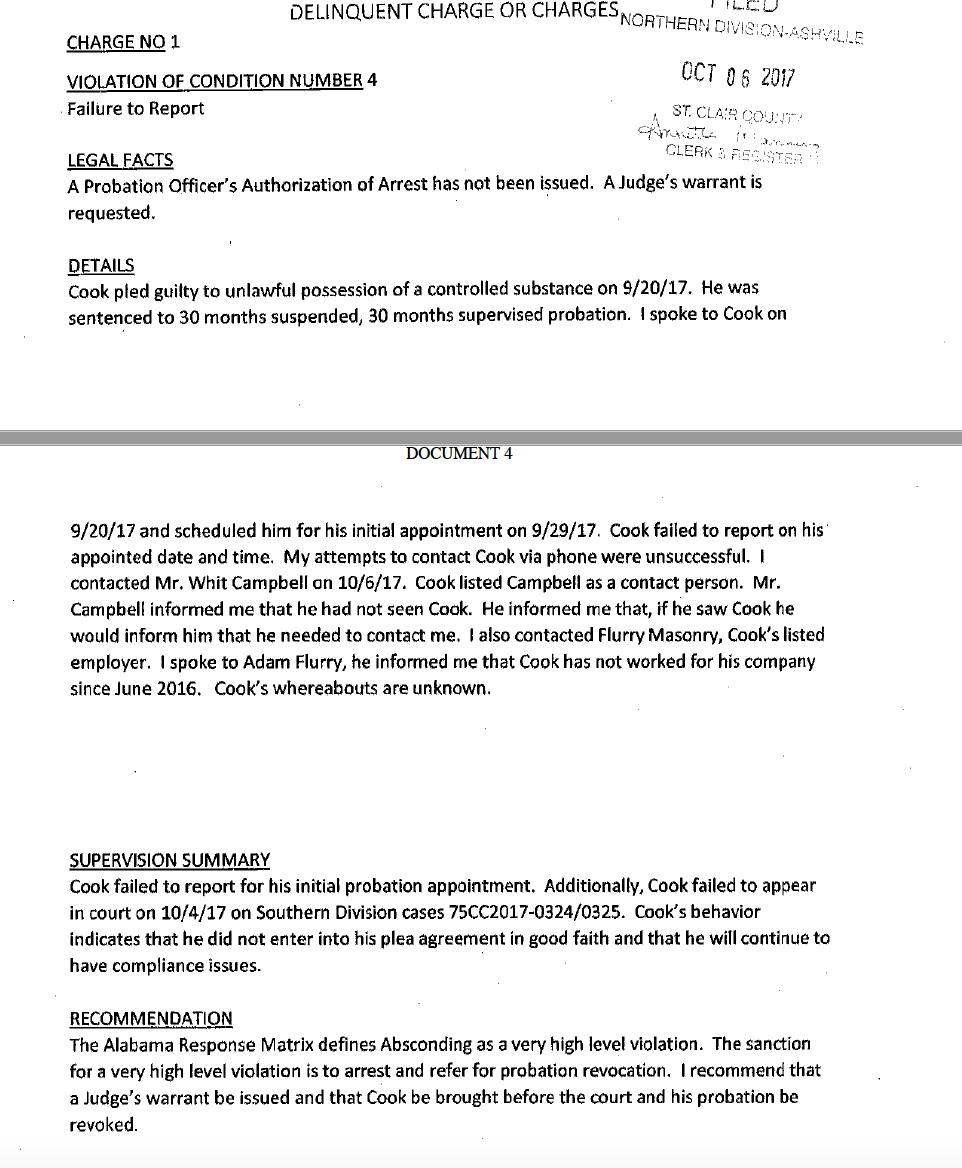

(Casey Cook before high school prom with Linda Golden’s daughter, Debbie Merchant. Golden said Debbie was like a mother to Casey. He lived with her on and off.)

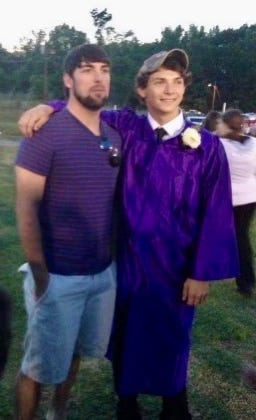

He began getting into trouble while attending school in Moody, so Gallahar relocated to the small town of Ragland where Casey graduated from high school in 2014. The rest of his life was a series of stops and starts—he left Ragland but stayed in St. Clair County, had a baby with his girlfriend, continued using drugs but made attempts at rehab, and ultimately became tangled up with the criminal justice system. Instead of putting him on a better path, it destroyed him. And that same system grinds along, actively destroying other people who are unlucky enough to get tossed in.

(Casey Cook at his 2014 Ragland high school graduation with Golden’s grandson, Erin Merchant)

Golden described a familiar process of learning about Casey’s death marked by terrible communication and a heartless response from prison leaders. Like so many other families whose loved one dies in prison, she first heard something bad had happened to Casey through other sources. While Golden wept on the phone, warden Patrice Jones confirmed his death, but came across as rude, vague, unhelpful.

Golden asked about receiving Casey’s belongings in the prison—some photos of his son she had recently mailed him and a journal he kept while attending the prison’s drug program. Jones insisted that his property was limited to basic items she read off a list—two t-shirts, shoestrings, underwear. Golden stopped her and asked Jones if someone could double check Casey’s bunk for the pictures and journal, but the following day when she asked Jones again about it, Jones replied that she’d already read her the items on his property list. Golden let it go.

“I really wanted the journal,” she said. “That would have been some personal notes that I could cling to and keep, see how he was feeling or what was happening to him.”

The family couldn’t afford the cost of shipping Casey’s body home for burial, so they had him cremated instead. Golden has submitted a request for his autopsy report with the Alabama Department of Forensic Sciences, but until she receives it, which could take months, she has to wait and wonder. She’s heard from sources in the prison that Casey didn’t intentionally overdose, that someone killed him or “laced him up,” giving him too much of something that caused his death.

“That could have been done while he was laying there asleep,” Golden said. She has no other information to go on, and ADOC has offered no help. The people that loved Casey have not only lost him, but also the reasons behind his death.

“Either he overdosed or somebody killed him,” Gallahar told me. “That’s the only things that could have happened because he was in good health. But they have told us zero as far as what happened to him in that prison, and I’ve got my hands up in the air. I don’t know what to do.”

Not knowing what happened seems to add an extra layer of pain and anguish—the shock of his death with the trauma of cruel indifference on top. It’s a rotten and inexcusable outcome that too many families in Alabama face. I’ve seen it again and again while covering this madness.

I wonder how Casey Cook’s death could have been prevented. I hear system actors like judges, lawmakers, even some prosecutors, speak the language of recovery. They talk about second chances, and providing rehabilitation in prison and how it’s wrong to criminalize substance use and mental illness. But they continue sending people like Casey Cook into Alabama’s horrific prison system, the worst place an addicted person can find themselves. And for many, like Cook, it’s the last stop in their lives. He deserved better, his family deserved better. His little boy who just lost his father deserved better.

Great reporting, and the photos help. Seems like in many cases the only photos available are the mug shots.

Casey Cook, I’m sorry man! I wish I’d been there for you more. Didn’t expect you to go so soon.

We’ve been waiting on you to get out so you could come back to work. I love you man!!

For everybody else I think it was BS he was even in such a facility because yea he some issues but he was a better man then a lot I know. Hard worker to. When he says he had a job waiting, he did. He did have a few issues he needed to get away from, and I know personally he was trying hard. Damnit I can’t believe this screwed up system ended his life. Casey had big dreams and with just a little help from the system he would have done great things. Instead they put him right back in the middle of what he wanted desperately to get away from. That’s a shame!

I grew up in the system I know how it works and what it can do. Hell they wanted Casey so bad they sent bounty hunters after him for a couple FTA’s. He didn’t have a chance because once you miss a couple dates because you don’t have the money to pay the fine because you have to live and eat. Your marked in the system and they won’t hear nothing you got to say. Lock him up with some shitty plea deal that was never in his best interest. But I know worse people with money that’s walking through the streets in st Clair co. right now!! SMH!!!