I recently had a startling conversation with an incarcerated man named Marvin. You can listen to an excerpt by hitting play on the link above.

Marvin told me about something I thought I knew about, but to hear him describe his direct experience on an Alabama prison chain gang shocked me awake. This ugly chapter in our recent history suddenly became less abstract, Marvin’s words painting my plain understanding into vivid color.

He has served almost 30 years in the Alabama Department of Corrections (ADOC) for robbery, an appallingly long sentence, but hearing him so casually recount the humiliation on the chain gang reminded me why Alabama cannot be trusted to follow the U.S. Constitution, not then and not now.

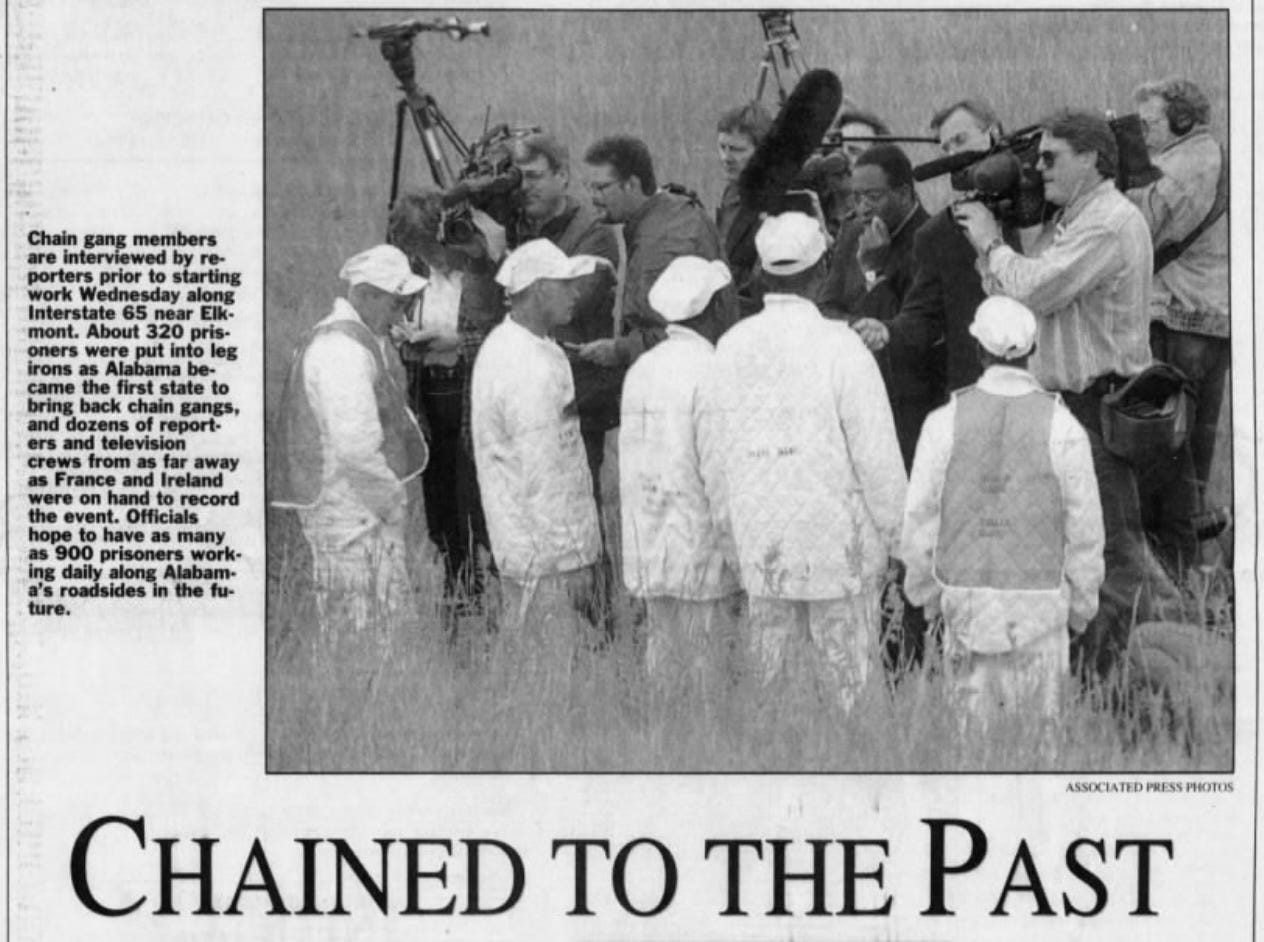

Marvin is a Black man from Huntsville. He entered prison in 1995, the same year Alabama revived the use of chain gangs, a practice dating back to slavery in which overlords chain human beings together, in this case, wearing leg irons and laboring on the side of highways for no pay, sometimes for 12 hours a day.

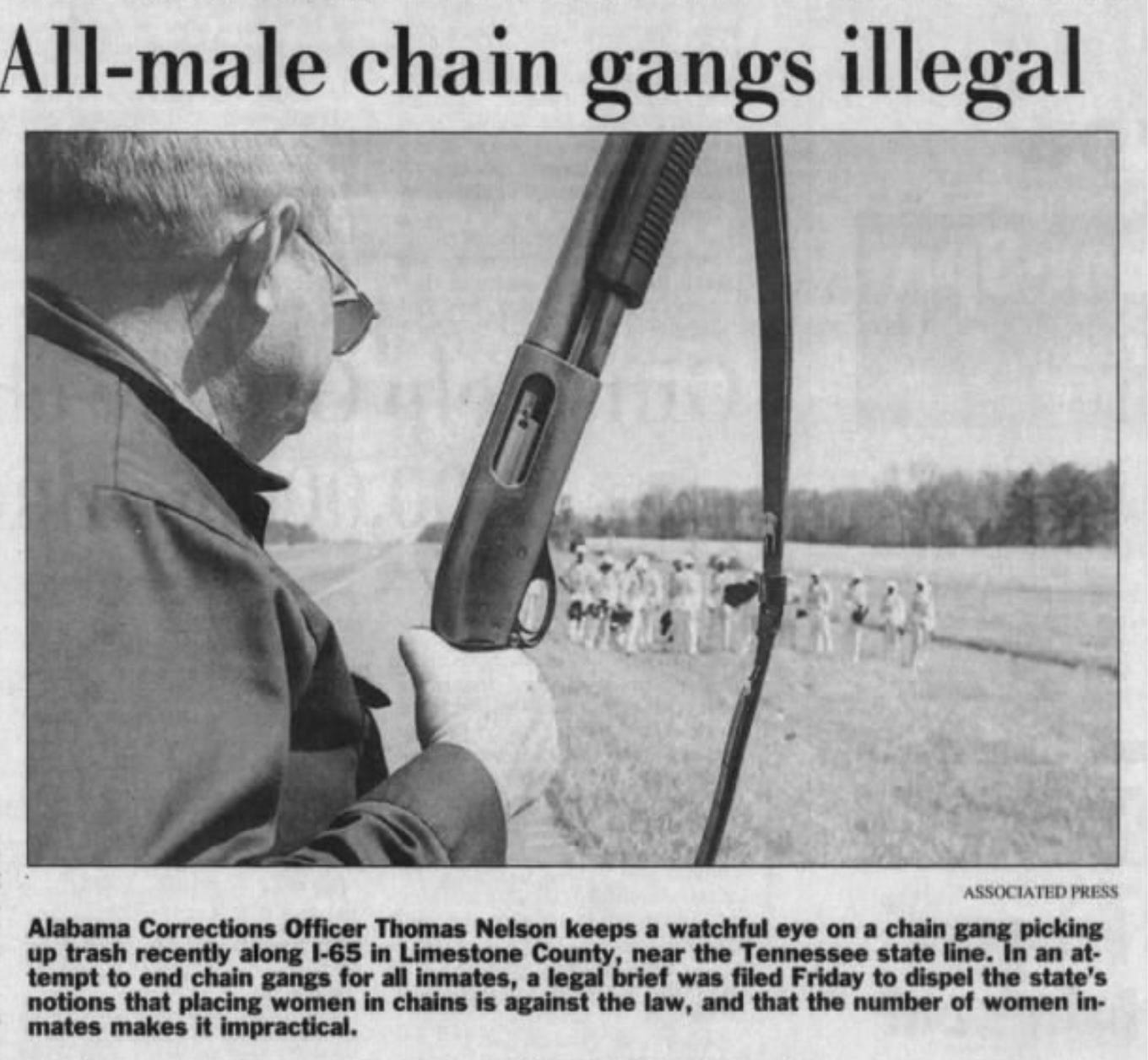

Guards armed with 12-gauge shotguns had orders to shoot anyone who tried to escape. They killed at least one man before a federal lawsuit ended Alabama’s use of chain gangs in 1996, just one year after then-Governor Fob James first floated the idea of resurrecting chain gangs during a political campaign event.

Marvin was 25 when he spent three months on the chain gang while incarcerated at Limestone Prison in the north Alabama town of Harvest. He remembers the officers on horseback with shotguns, barking orders as the men, chained together in groups of five, struggled to walk together and not lose their balance.

“If one guy went right and you went left, then that would mess your ankles up,” he said. “You could even break your ankles like that.”

The work included chopping down weeds and brush in the blazing sun and breaking up big rocks with sledgehammers, “like in the Flintstones.”

Marvin recalled a time they were forced to wade into waist deep swamp water, then scrambled to get away from snakes. The officers didn’t care about such hazards, Marvin told me, they shouted at the men to continue working and one fired a warning shot into the air.

“He said, ‘The next shot, I’m gonna kill somebody.’”

This throwback to antebellum times was occurring when I was a 20-year old college junior across the state, completely oblivious that this modern form of slavery was unfolding in my name, on my dime.

Of course, I didn’t have to know about this because the vast majority of people forced onto the chain gang were poor and Black, not from families or communities that intersected with the privileged existence I enjoyed.

I don’t recall hearing about Alabama’s revival of the chain gang in 1995, despite international news coverage, and I am sad to admit that I’m not sure my narrow bird brain would have cared. I was too busy partying, having a good time, strategizing on my own ambitions and plans that didn’t include deep concerns for fellow citizens who didn’t look like me.

Thankfully I have grown up and evolved, priorities have changed. My ongoing reporting about Alabama prisons is what led Marvin to get in touch with me, and thus, this conversation about the chain gang.

I’m interested in Marvin’s story because I’m collecting accounts about prison labor, the subject of a class action lawsuit filed in December of 2023, on behalf of Black citizens who argue ADOC, Governor Kay Ivey and the state’s parole board are conspiring to traffic in a modern-day form of slavery that allows government agencies and private businesses to enjoy financial benefits of $450 million annually, by paying workers far below prevailing wages and subjecting them to wage garnishment “to assist in defraying the cost of his/her incarceration.”

If you don’t know, the Alabama Department of Corrections (ADOC) includes 12 minimum-security “work release and community work centers” that incarcerate over 3,100 people. In theory, these facilities are supposed to be the last stop, preparing incarcerated people for release with skills and earnings by placing them in jobs throughout communities.

In practice, these are really forced work camps that exploit incarcerated labor, a carrot and stick the state uses to claim it’s good for the incarcerated person because it prepares them for release. However, the parole board refuses to grant relief to almost everyone who qualifies, which means release will likely never come, and minimum-security laborers could toil away in these grunt jobs for years, even decades.

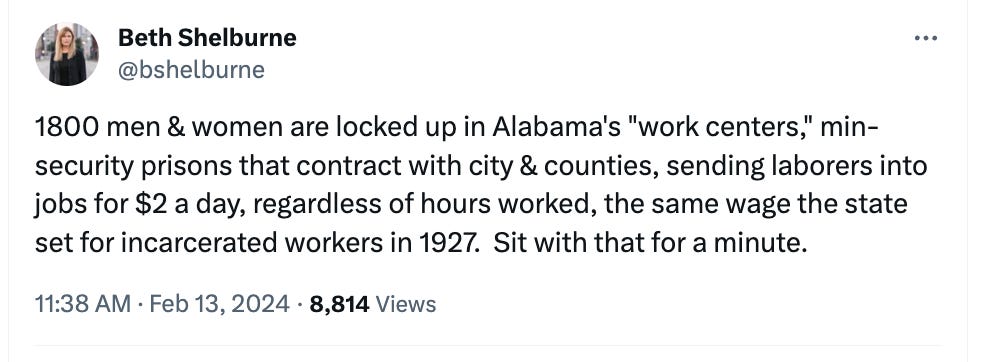

ADOC keeps 40 percent of earnings from those in work release, who typically work for private businesses like fast food restaurants and manufacturing companies. Work centers, meanwhile, lease workers to government agencies while ADOC pays them just $2 a day, the same wage the state set for incarcerated labor in 1927.

When Marvin’s time on the chain gang ended, he was transferred to a “farm squad,” yet another iteration of forced prison labor, “only difference was I didn’t have chains on my ankles,” he said. His squad worked ADOC land, clearing brush, trees and weeds for long days in the sun. As they went to work in the morning, the prison issued a sack lunch for each man that contained just two to three thin sandwiches, precious little food to fuel an entire day of manual labor.

“And we were doing all this free of charge,” Marvin said. “We weren't getting paid. Not a single nickel.”

Marvin’s account of forced prison labor matters because Alabama’s exploitation of prison labor didn’t end, it just evolved. The state may have agreed to stop chaining men together, but it still forces people like Marvin into dangerous work with degrading conditions. And unlike all other workers in the United States, these men and women have no recourse.

Marvin lost his work release job assignment after a co-worker at an industrial plant called him a racial slur and he reported it to his supervisor. Instead of addressing the problem of racism in this workplace, ADOC transferred Marvin back into a medium-security prison, where he sits, day after day, waiting for his sentence to end.

This is just one example of the punishment incarcerated workers face if they speak out about mistreatment or dangerous work conditions. The lawsuit argues ADOC retaliates against workers who voice such concerns by citing them for “refusal to work,” then taking away privileges, sending them back “behind the walls” of violent medium and maximum-security prisons or even banishing them to solitary confinement.

Alabama’s choice to resurrect chain gangs in 1995 wasn’t just a political hiccup, it had widespread support from the population. Public approval seemed to embolden the instigators, like prison commissioner Ron Jones.

"I'd like to have some real electric fence," Jones told a European journalist in 1995. "Around 5,000 volts. That's what you'd call extremely lethal. I think we should think about caning as well. Some of our inmates come here with very fixed attitudes."

And indeed, ADOC leaned in on the brutality by punishing people who refused to work on the chain gang by cuffing them to a hitching post with no water or bathroom breaks. Yet another barbaric practice that only ended through litigation, not the moral suasion of citizens.

Marvin reminded me the only reason that ADOC agreed to cease chain gangs was because of federal court intervention. If it wasn’t for that, he said, Alabama would still have chain gangs today.

“This was all a form of punishment, just because we was incarcerated,” he said.

”They were taking full advantage of all of us.”

And those suing the state over the current practices of forced labor would argue Alabama still takes advantage and exploits incarcerated citizens. And they have once again placed hope for change with the federal courts, knowing Alabama will continue its brutal practices as long as citizens look the other way, and it can get away with it.

When my son first went to prison at GK Fountain he had to work on the farm picking tomatoes and at the time he said that he never wanted to see another tomato, the facility did use them for food but also sold them and peas also and when he was transferred to limestone it was the same . In January 2022 he went to Elba work release and was paid 2 dollars a day working on a road crew then later as a mechanic for pike county road department, if the road crew was short he would be pulled to there for a day or two , after being there for 5 months he came up for parole and was denied although he met all the guidelines and he was set off 4 years and continued to work and in January 2023 he started getting sick and for six months would not do anything for him and as a nurse I knew he had all symptoms of cancer and he told the dr there, he had a mass in his right lower abdomen that was the size of a baseball, I felt it and he was losing weight, having abdominal pain and diarrhea, classical symptoms they sent him to Easterling for X-rays twice but did nothing and gave him nothing , he was eating ibuprofen and Tylenol, he was sick in bed a week and they did nothing ! His boss sent word that he needed him and he worked sick until July 28th he was sent back to Easterling, long story short never received treatment, he’s passed now but they will use you until you’re no use to them anymore and yes he was given the vaccine a year and half before he became sick and I question that also. Men need to be treated as human beings not work horses! If they work pay them fairly so that they feel like they can do something for themselves not just the family supporting them! They are someone’s son , husband, brother, uncle , grandson, nephew and need to be treated with dignity and not as a slave period!