I try hard to ignore the people on Twitter who call me names—Karen and Libtard are two favorites, but when people write what appears to be a sincere criticism, I sit up and take it in. This week I noticed a response to one of my many exasperated tweets about our messed-up criminal justice system. Right there between all the likes, shares and quote tweets, someone called me out. And this is someone who is currently locked up in prison.

“You my friend are doing absolutely nothing,” he wrote in response.

I stared at the screen and felt a twinge of hot-faced shame. Looking out the window in my comfortable, sunlit office, I silently asked myself What exactly am I doing?

“Tell me more about why you think this,” I wrote back. I sincerely wanted to know, needed to know. He responded two days later.

“What I mean is way too much talk,” he wrote. “I understand that there is only so much one can do, but words aren’t saving our lives here. It's going to take some kind of action. By no means am I calling for anything violent, but we are dying here and no help is coming.”

People in our prisons are not supposed to be on social media, they’re not even supposed to have access to the internet, but because corrupt officers traffic in overpriced cell phones, you can find plenty of online content created inside the prisons.

It’s something I have grown to appreciate, because much of this communication serves as a bridge between those of us who want to understand what’s happening inside and the people who are actually living it.

Case in point was this sledgehammer of a twitter response written by someone who is living inside the prison crisis.

WAY TOO MUCH TALK. WORDS AREN’T SAVING LIVES. WE ARE DYING HERE AND NO HELP IS COMING.

I understand why he feels this way. The gaping disconnect between his experience and the response from government bureaucrats has never been more appalling.

This past week, on the heels of the deadliest year in the history of Alabama prisons, Governor Ivey issued an executive order making it harder for people to get out of prison alive.

Executive order 725 made changes to rules surrounding correctional incentive time, better know as “good time,” taking discretion away from individual institutions and expanding the ways an incarcerated person can lose their good time, sometimes permanently.

Notably, the violation of “encouraging or causing a work stoppage” will now be considered a high-level violation, on par with fighting with a weapon or committing robbery. The punishment for such an offense includes loss of all earned good time and banishment from earning good time for one year.

The legislature has already passed laws excluding most people in prison from earning good time. Only 13 percent of the population is currently eligible, and this expansion of sanctions makes it harder for the few thousand people left who might be able to shave some time off their sentence by keeping their heads down and avoiding trouble, an unthinkably difficult feat in facilities packed to the rafters with desperate people, surrounded by drugs and organized crime.

The press release issued by Ivey’s office was an incredible piece of propaganda, suggesting that good time has created a crime wave and that cracking down on it will improve public safety.

Senator Clyde Chambless, seen in the photo behind Ivey, gazing at her as she speaks at the podium, said the changes would target those in ADOC custody who are “gaming the system.” Let’s be real, OK? Anyone locked up in prison is rendered completely and absolutely powerless at the hands of the state. They can’t game the system any more than a single ant can stop a lawnmower from obliterating their ant bed.

Ivey’s stunt was an act of political pandering, intentionally planned for National Law Enforcement Appreciation Day. But it also stretched her cognitive dissonance to new lows, ignoring the lawlessness and crime inside the prison system while claiming dedication to law enforcement, safety and justice. “We will not stop pursuing our goal of being the safest state in the nation and a sanctuary for law enforcement,” she said. Is that what we’re doing?

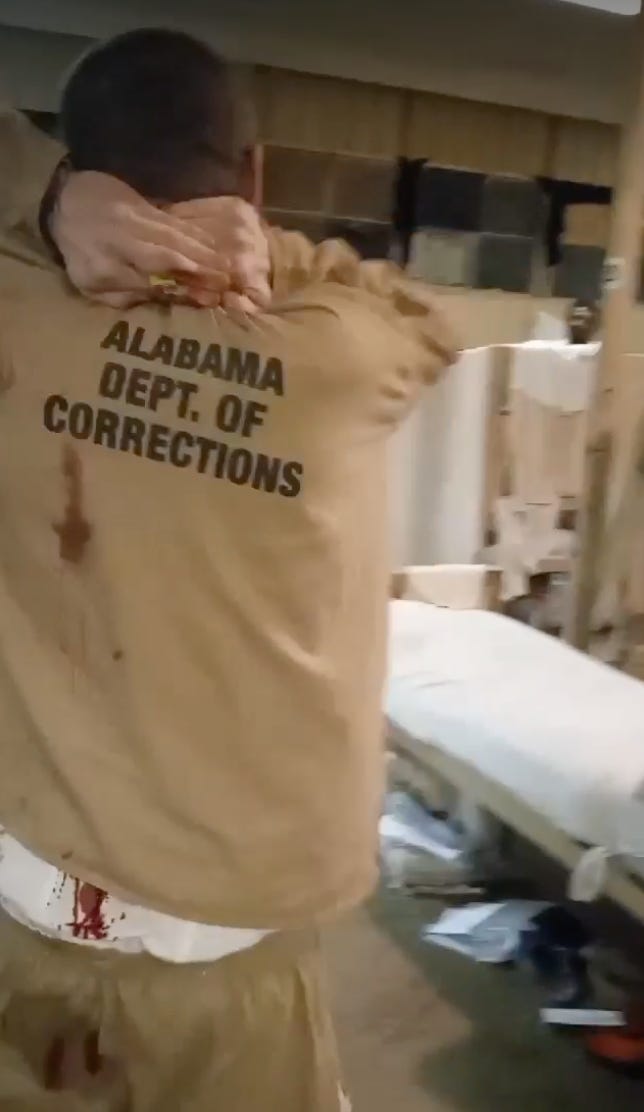

(A man bleeds inside an ADOC open dorm. Image is from video of an assault shared on social media.)

But maybe calling attention to all this BS amounts to nothing more than word salad. I think back to the incarcerated citizen who called me out on twitter and I ask myself, is all this writing and reporting about the prison crisis meaningless? What if he’s right? What if everything I think I’m doing really amounts to absolutely nothing?

Writing and reporting is what I know how to do, but maybe it’s time for me to think about doing more. Sure, creating words isn’t the only thing I do—I speak publicly about the crisis, I try to spread the word about ways people can get involved, I support organizations working to curtail suffering and free people from ridiculous sentences.

But at this point, maybe I’ve said all I can say. I’m no longer at the edge of a tsunami, I am in it. So do I keep writing about the tidal wave? Or do put my pen down and try to save lives? How can I pull people out of water before they drown?

What can any of us do other than feel outraged? I sincerely want to hear from you, all of you, about how we can approach this crisis beyond words. Let’s listen to my friend in prison because he’s saying what we all need to hear.

Words can save lives, but particular kinds of words can do more than others. The words which can have the most power fall under a 2 word descriptor: Investigative Journalism. I applaud your efforts to bring greater justice and compassion to Americans suffering in our abominable, intolerable prison system. Perhaps the kind of writing which has the potential to do the most good is uncovering facts which others want hidden and which cannot be ignored once they are exposed. Bring down the corrupt guards and corrupt wardens who are violating the law. Expose the horrendous conditions. Seek out new FACTS rather than simply advocate against the problem. That is the great power that we can do with our pens. Keep up the fight!

Thank you Beth for all you do to help expose this problem with the Alabama Department of Corruptions.