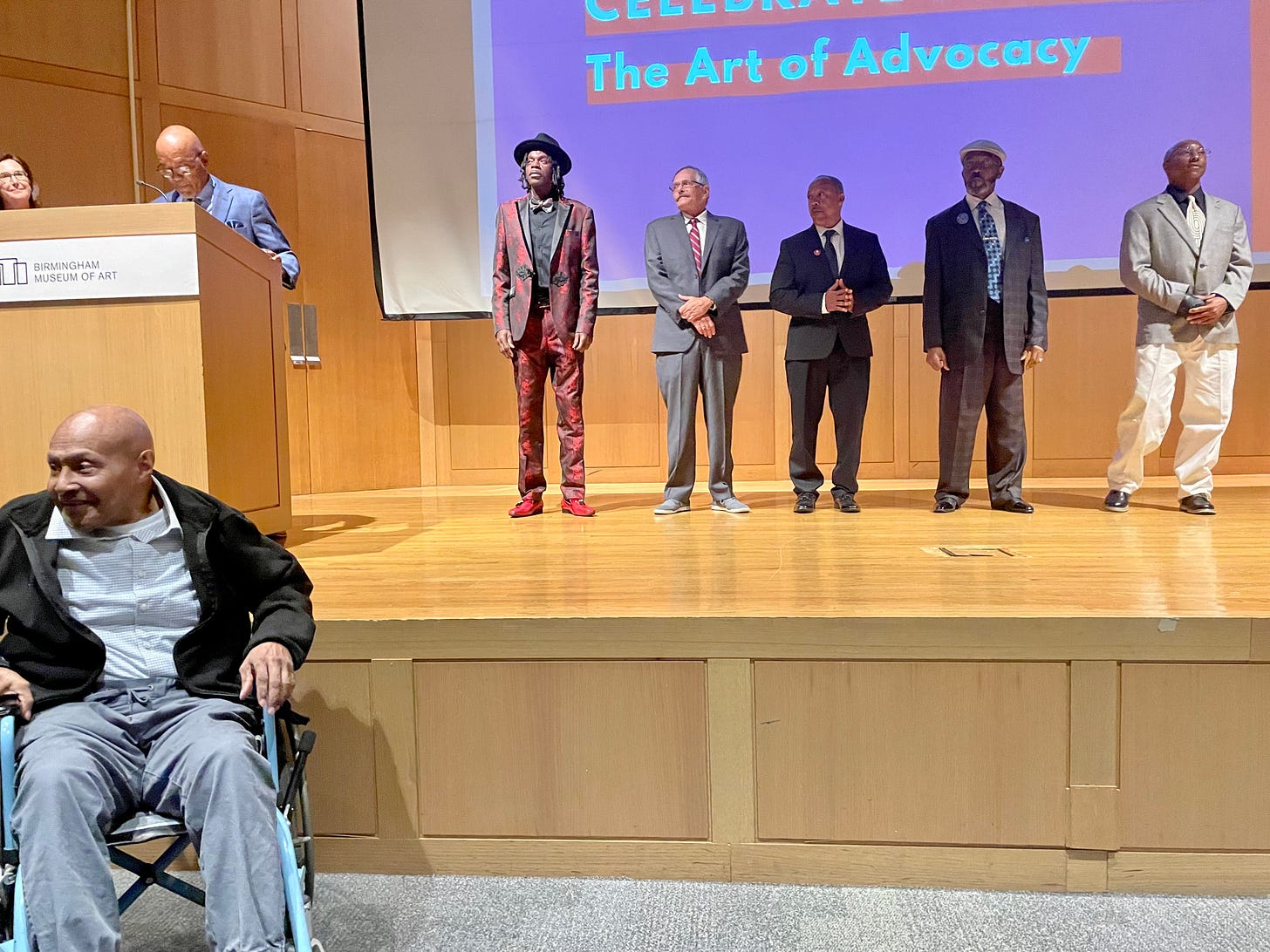

(L-R Robert Cheeks (seated), Ron McKeithen (podium), Alvin Kennard, Michael Schumacher, Motis Wright, Alonzo Hurth, Joe Bennett)

Last week I joined over 100 other people at an event put together by Alabama Appleseed that honored seven men freed from prison in the last three years. All were represented by dynamo lawyer and my friend Carla Crowder, who is Executive Director of Appleseed. Before she worked as an attorney and organization leader, Carla was a journalist who wrote extensively about Alabama’s horrible prison system and habitual felony offender act (HFOA), our wretched version of a 3-strikes law that mandated all of these men to die in prison for crimes that left no one physically injured.

I first began researching Alabama’s HFOA around 2014 when I met Ron McKeithen, who was 30 years into his sentence at Donaldson prison. We met while I was covering an educational program at Donaldson, and I was shocked to learn Ron had such a severe sentence for a short list of convictions—third degree burglary, credit card fraud and a single robbery.

When I began drilling down in archival news coverage trying to figure out this law, I found many of Carla’s previous stories. Long before I started writing about the impact of this law, she was sounding the alarm. Carla is my sister-reporter—we both have the unique experience of attracting indignation from certain readers simply for telling the truth about the horrors of incarceration. This infuriates some people, who suggest that we don’t care about crime victims. I’ll never forget the Facebook message I received from a local cop who said that he used to think I was a good person, but he’d lost all respect for me after I started “taking the side of scumbags.”

In 2014, Ron and I exchanged a few letters, but three years later when I decided to focus on Alabama’s HFOA for my graduate thesis project at UAB, Ron whole-heartedly agreed to collaborate and answer any and all of my questions, nothing was off limits. This resulted in dozens and dozens of letters, enough to eventually fill up two binders that I happily gave back to him earlier this year at the Appleseed offices where Ron now works as a re-entry coordinator. For me, those letters were a master class in getting proximate to injustice, a necessary practice according to Bryan Stevenson, who says, “We cannot create justice without getting close to places where injustices prevail.”

As I encouraged Ron to peel back the layers on his story, I was learning about my own relationship to the system as a privileged person who worked in the media machine. Our letters felt like a deeply creative exercise, but they were also crucial in helping rip the blinders from my eyes and snap me to attention. I learned there was nothing fundamentally different between Ron and me. The more and better I knew him, the more outraged I became. He is a beautiful human being and our system had thrown him away.

The generosity and time Ron put in those letters was a gift to me, one that I wish I could package up and give to those in power who don’t seem bothered that hundreds of other people, mostly Black men, are serving death-in-prison sentences in Alabama’s overcrowded, violent prisons for similar convictions. I naively thought my writing about Ron and others might move them, but I realize now it’s not enough. They must be open to receive such a message, but it would likely only land through personal experience. Nothing changes a hardliner outlook like some skin in the game.

When I began to cover Alabama’s prison crisis in 2012, I knew very little about the reality of what it’s like to be arrested, prosecuted or incarcerated. What I knew was vastly limited, like looking out a small round porthole on a sinking ship and only seeing a narrow view of the sky, while missing the expanse of churning sea and all the people around me struggling to keep their noses above water. Getting proximate to Ron and others is what opened up what I didn’t know and invited me in.

At the time, I had dreams of discovering entire rooms in my house that were previously unknown to me. I would turn the corner and suddenly be in an unfamiliar room and think, was this always here? This vast, unusual room, this expanse of ceiling and walls? What are all these objects draped in cover? This dream wasn’t a treasure hunt, it was more like a becoming, an understanding that I was only just seeing a place that had always been there, I just hadn’t bothered to turn the knob, or even see the door. But once I was there, I couldn’t un-there there. It was impossible to un-be, un-dwell, un-see.

I consider myself a deeply empathic person, so getting proximate to anyone or anything isn’t a challenge for me. But I realized on a recent trip to New Mexico that proximity can make some people uncomfortable. In Sante Fe, I visited the iconic Georgia O’Keeffe museum, and while I was taking in her exquisite flowers and landscapes, I read that her paintings and pastels focused on the centers of flowers were considered controversial when she created them in the 1920’s. I’m not referring to the contemporary sexualization of these works, comparing the imagines to vaginas. A century ago, critics were unnerved by their intimacy. Admiring a flower from afar was fine, but going inside the flower? That felt like too much. O’Keeffe explained:

“A flower is relatively small. Everyone has many associations with a flower, the idea of flowers…. Still, in away, nobody sees a flower—really—it is so small—we haven’t time—and to see takes time, like to have a friend takes time.”

(Taking in O’Keeffe’s 1930 painting titled “Black Hollyhock Blue Larkspur”)

So what am I getting at here? To know Ron and the other six men honored by Appleseed last week is to also know the injustice they faced and our responsibility in owning this system we’ve created. Not everyone is ready or willing to sit next to that, or to go inside this vast room we’ve been pretending isn’t there. People who haven’t been proximate to individuals like Ron or Michael or dear Mr. Robert Cheeks do not know what they do not know. Their perception and beliefs are limited to the information they access, and if it’s strictly local media, chances are the view they have of justice-involved people is really, really, really bad.

I started to write a newsletter about my apoplectic reaction to a recent statement from a cabinet member of Governor Kay Ivey that the 98 people locked up in Alabama prisons for weed convictions amounts to “almost no one,” but I stopped myself. Voicing more outrage over a view of human lives in terms of numbers isn’t going to build a bridge. The men we celebrated last week—Ron, Mr. Cheeks, Alvin, Michael, Motis, Alonzo and Joe—they deserve to be celebrated and uplifted and amplified, all of them are leading successful lives despite the decades of corruption and cruelty they endured.

Each of them is so much more than mistakes they made that led them to prison and I’m grateful to know that. I’m proud to keep trying to invite more people to consider what and who they don’t know and potentially open their eyes to the best of humanity and redemption and not the same old worn out, tired trope of do the crime, do the time. The same old ways of thinking, denying the experience or existence of others that’s behind the construction of new prison walls. That should be the thing that makes us all uncomfortable, not the center of flowers or the men and women worthy of redemption, waiting to be seen and given a chance.

Thank you, Beth, for this excellent report. Words fail me.

Great post Beth. I'm not surprised about the comment the law enforcement officer said to you. Before i retired I worked for a local city. My job was computer support for the police department. Most of them had that mind set. There were a few that I think were really good officers.