Following Alabama's Blood Money

Prison lawsuits, payouts, and how lawyers for abusive officers hit pay dirt.

Follow the money. That’s always the advice in trying to unravel any complicated story involving corruption, including the deadly crisis inside the Alabama Department of Corrections (ADOC). So I spent 16 months doing just that, specifically following the millions connected to lawsuits over horrific prison conditions, and the results—a 4-part investigative series called “Blood Money”—was just published in the Alabama Reflector.

The grotesque violence exposed in these bloody lawsuits depicts a prison landscape that features subterranean brutality, and a power structure that continues to publicly deny Constitutional violations inside state prisons, while routinely and quietly paying settlements in lawsuits filed over the exact same violations.

Key findings of Blood Money:

ADOC has paid settlements in at least 124 civil rights lawsuits since 2020, the vast majority (94 of 124) filed over excessive force.

Almost half of the incidents resulted in injuries so severe the victim required hospitalization, including broken bones, wounds needing surgery and head trauma resulting in brain damage.

The cost of this litigation pushes ADOC’s total legal spending since 2020 to a stupefying $57 million. And it’s the lawyers defending accused officers, not the prisoners who’d been harmed, getting the lion’s share of that money.

10 officers accused of violently assaulting prisoners still work for ADOC, and 5 were promoted after being sued for excessive force.

The specific money I followed for this reporting is the bucket of public dollars known as Alabama’s “General Liability Trust Fund,” which is similar to insurance. The fund pays for the defense of state employees who are sued, as well as any potential settlement to the wronged party. ADOC is currently litigating an unprecedented onslaught of lawsuits filed over excessive force, wrongful death and failure to protect from harm, bleeding millions from the fund. Prison experts call the volume of litigation and paid settlements “extreme” and “inconceivable.”

The seed for this project was first planted in 2016 when I wrote a story about a single prison lawsuit against ADOC that cost the state $1.5 million in legal fees, which I discovered was triple the amount that ADOC submitted to the legislative oversight committee that monitors contracts between state agencies and outside vendors. While reporting that story, a source told me that ADOC routinely paid settlements to prisoners and their families who sued them, instead of taking the cases to trial, and taxpayers were footing the bill.

How do I find a record of the settlement payments? I wondered. My source didn’t know, but her tip intrigued me, and for years I tried to figure out how to track this unchecked spending. I knew there was no record of these settlements coming out of state’s general fund, because Alabama (amazingly) publishes those transactions in an online database called Alabama checkbook. I also knew terms of the settlements, including the amounts, were not included in court records. I was stumped.

But I kept asking, and continued to poke around. I wrote other stories, worked on different projects, but I didn’t lose that initial prickle of curiosity, and my spidey sense told me that there was a big story in those numbers, if I could just find them. I wanted to answer all the questions swirling around the unknown: How many lawsuits? What were they filed over? How big were the settlements? What did it mean when a lawsuit settled? And could these lawsuits further pry open the trap doors on information that ADOC preferred to keep locked tight forever?

About two years ago a breakthrough came. My colleagues on the upcoming HBO documentary film “The Alabama Solution,” on which I serve as co-producer, located a record of the settlement payments. They shared with me that settlements were paid out of this special liability trust fund, and because that’s a public resource, it was subject to FOIA, which meant I could file an open record request to the state finance department, which manages the fund, asking for the receipts.

I did not know what I was getting myself into, but I pursued it anyway. After receiving the first spreadsheet of payments from 2018-2020, I applied for a grant from the Fund for Investigative Journalism, which provided $10,000 to support my reporting. I estimated it would take a few months, but nay, I was way off. Sixteen months passed between the time I secured the grant and when the series was finally published. I was grinding away at this for over a year.

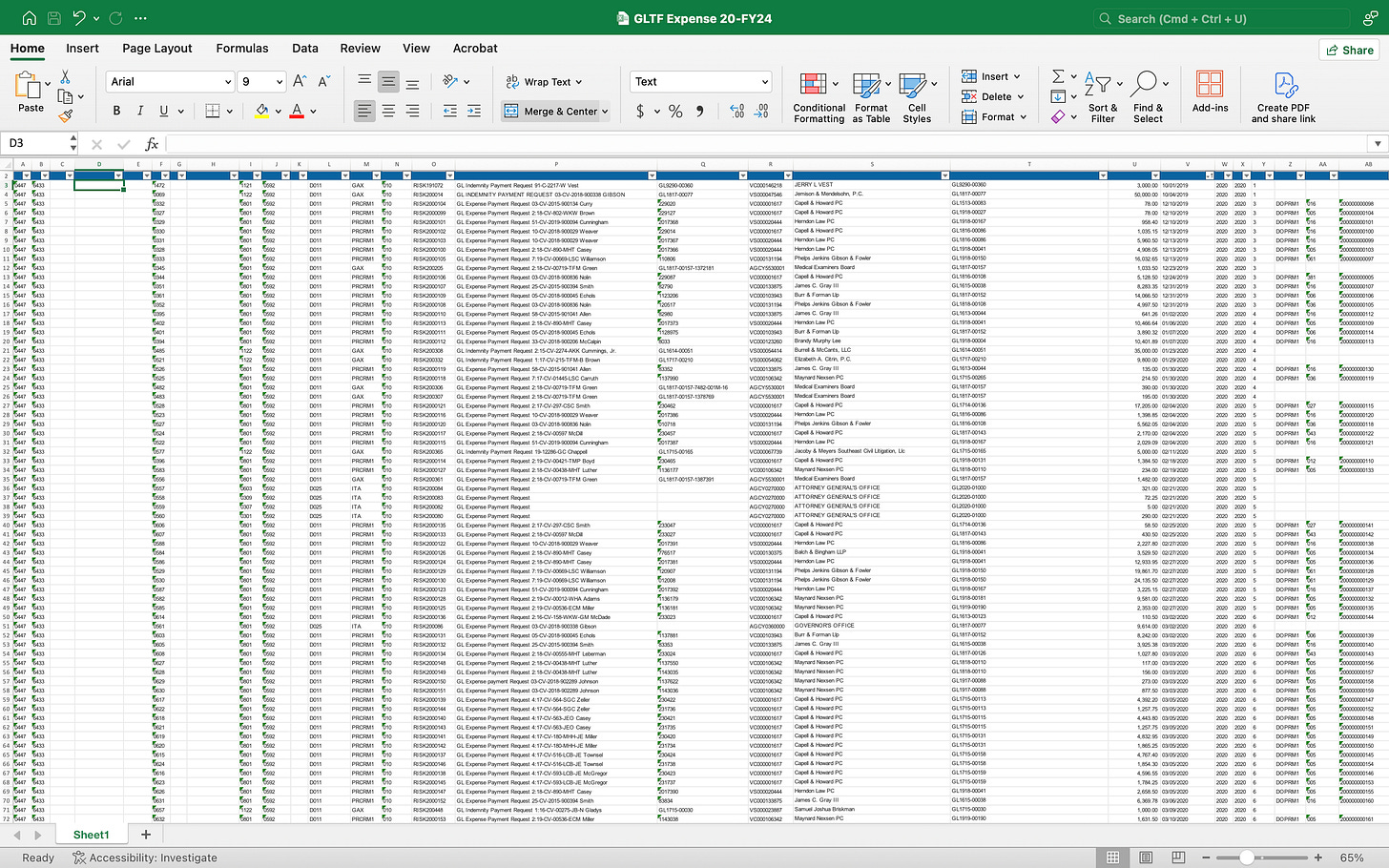

To call this project tedious would be an understatement. So complicated, in fact, we included a “How we reported Blood Money” explainer about the investigative process— which included analyzing multiple spreadsheets of transactions that I obtained from the finance department’s division of risk management, and trying to make sense of this arcane accounting data. There was no blueprint to follow, no similar reporting to imitate, no database of comparable information from another state to consult. I had to figure it out as I went along, but it felt like a giant puzzle that I was determined to solve.

The spreadsheets of transactions included both legal expenses to attorneys and indemnity payments, another word for paid settlements. These transaction records contained corresponding case names and numbers, which allowed me to connect each transaction to specific lawsuits that I located in federal court records. In reading and reviewing the complaints, I was able to pinpoint which transactions were connected to lawsuits involving ADOC employees. All told in the data, I identified 124 lawsuits against ADOC employees that resulted in paid settlements between 2020-2024.

The accounts in these lawsuits were harrowing. The majority of the original complaints were handwritten by incarcerated people inside the prisons, and to read the descriptions of these brutal assaults, written in their own voices, often while they were still traumatized or in crisis, felt hauntingly intimate, like I was reading personal letters, missives from hell. The fear for their lives that they expressed chilled me, which after 13 years of reporting on prisons is not easy to do. And the volume of violent assaults was simply staggering. Men were getting beaten and brutalized inside every major facility in the system, and even in some minimum-security work release centers. Some of the incidents sounded more like gang violence than excessive force.

I used these 124 lawsuits as a fixed cohort to study, to not only look for trends and patterns in the allegations, but also the time and money spent using public funds and resources. From a broader perspective, the volume of lawsuits resulting in paid settlements affirmed what we already knew to be true—that Alabama prisons are death camps. While ADOC was quick to say a paid settlement is not an admission of wrongdoing, I don’t see anyone questioning who is liable when prison guards beat a prisoner into a coma, which was the case in at least 7 lawsuits.

It’s also important to recognize that these are not frivolous complaints. Before the state even thinks of offering a paid settlement, a lawsuit must pass several procedural hurdles and scrutiny from a federal court. Typically settlement talks begin only after a court denies ADOC’s motion to dismiss the lawsuit, allowing the case to proceed closer to trial. This can involve years of litigation, and the private lawyers hired in no bid contracts to represent the accused guards bill the liability trust fund for every minute of it.

In fact, of the $17 million connected to lawsuits I tallied up during this time period, almost $13 million went to lawyers for the guards, while paid settlements added up to just $4 million. Prisoners who sued over excessive force received a pittance, with the median settlement at $8000. And because the liability trust fund caps each case at $1 million, attorneys for the guards can drain the funds available for a settlement, treating the liability fund like their own personal revenue stream.

“These outside attorneys have every incentive to bill the shit out of the fund,” said attorney Hank Sherrod, who represents prisoners in civil rights cases. “Using outside law firms billing by the hour can make the GLTF (liability trust fund) more of a pot of gold for law firms than a fund to compensate victims.”

Alabama’s Attorney General Steve Marshall directs the legal defense for ADOC employees, and did not respond to repeated emails, phone calls or the list of questions I submitted to his office for this reporting. I did finally speak with an assistant attorney general in the finance department, Daryl Masters, who manages the general liability trust fund for the state division of risk management. He soberly answered my many questions, explaining that the priority from his end was strictly administrative.

“The agencies themselves are the ones who are responsible for dealing with any particular type of claim,” Masters told me. “Our end is more about the numbers.”

So according to the state’s division of risk management, the job of managing the risk of abusive guards falls to ADOC. This story, in many ways, is one about dysfunctional government as much as institutional abuse. Mr. Masters said something else during our conversation that I haven’t been able to shake.

“I know you want to report on this,” he said, “but I hope your article doesn't point out to enough people that want to jump on the bandwagon and get some more money out of the GLTF. That's that's our fear sitting here today more than anything else.”

I watched the livestream of this week’s prison oversight meeting in Montgomery, led by a committee of five state lawmakers. They didn’t mention the findings reported in Blood Money, which wasn’t surprising. Messages I left with half a dozen lawmakers in the past month went unanswered, and for years, I’ve gotten nothing but crickets from Governor Kay Ivey.

Her focus is strictly on the construction of her billion dollar mega-prison, the “Kay Ivey Correctional Complex,” currently requiring 1000 workers in Elmore County. I’d love to know how many of those laborers are people incarcerated in minimum-security “work release” prisons, being forced into the work of expanding mass incarceration in Alabama.

If citizens don’t care that state prisons are modern day slaughterhouses, maybe they’ll care about the flagrant misuse of their tax dollars, which always seem to be in short supply when it comes to actual, real needs in the existing system. And in the spirit of transparency, at least this information is now known, as opposed to hidden, unreported, ignored, forgotten. The silence from state leaders, while disappointing, is no reason to stop shining a light on this disaster.

A few weeks ago, I was talking on the phone with a source, a man incarcerated in one of Alabama’s terrible prisons, when shouting suddenly erupted on his end and he went quiet. I sat on the line listening to a single deep voice bellowing a string of admonishments punctuated repeatedly with, “I DON’T GIVE A FUCK!”

The tirade continued for about a minute, my source later explained the guard was defending the volume he uses when he calls the men to breakfast, which he apparently does at the top of his lungs. This tirade was the guard’s response to a prisoner who asked that the guard not shout maniacally first thing in the morning. He apparently didn’t GIVE A FUCK about what the men wanted, or needed, and threw a temper tantrum to make sure they knew it.

In the relative quiet since Blood Money was published, I keep hearing that guard’s hostile screams in my mind. I DON’T GIVE A FUCK! I DON’T GIVE A FUCK! I DON’T GIVE A FUCK! Maybe that’s a more honest take on this than the radio silence from officials in power. But I think the silence is worse.

So here’s where we stand: ADOC has spent $57 million and counting of our money on lawyers to defend this wretched prison system with no end to the bloodshed. State leaders seem to view this blood money as simply the price of doing prison business, and the lives of Alabama’s incarcerated citizens “as a sunk cost, a string of numbers to go on a spreadsheet,” as Alabama Reflector editor Brian Lyman wrote in his latest column titled “Mayhem, violence and death — but not ‘corrections,’” arguing that ADOC, by every standard, has failed its mission. I agree.

But I’m glad to put this series into the world. If you are interested in pursuing a similar project in your state, please contact me and I’m happy to offer guidance or technical assistance. And if you care about the way we treat our most vulnerable citizens, and the insidious ways your tax dollars are being spent to line the pockets of private attorneys, please read and share this series.

Part one: ADOC pays to settle nearly 100 lawsuits alleging excessive force

Part two: In wake of excessive force allegations, some officers got promoted

Part three: Koty Williams, the anatomy of his lawsuit and the aftermath

Part four: Costs of prison litigation rise, while private attorneys reap rewards

I was surprised when I read the term “relative silence”. I was sure from the first installment that this series would result in huge public outcry, given how much we care about our tax dollars. Can you clarify whose silence you are referring to? Politicians, public, media, all of the above? So does nobody give a fuck?

Thank you Beth for continuing to dig until you found this layer of depravity in ADOC. I too hoped hearing about the injustices would move the general public, that didn't seem to make a difference. Maybe the tax waste (lawyers fees) you've uncovered will move more of us to speak up and do something.