AL’s parole board: Leigh Gwathney (L), Dwayne Spurlock (middle) and Darryl Littleton (R)

I’ve been trying to come up with another term for Alabama’s parole board, and right now I’m settled on “punishment bureaucracy,” a term I first read in writing by Alec Karakatsanis, whose excellent newsletter about “copaganda” in our media is among my recommendations. I like the ring of it because it captures exactly the two areas where this board is excelling—punishing fellow humans who are already suffering in our unconstitutional prisons and sucking up a bunch of state resources with little output. Punishment bureaucracy describes them perfectly.

The current board, and the entire apparatus that supports it for that matter, is really a sham, a hoax, a fraud that puts on a pageant three times a week in Montgomery where parole hearings are held, but these are not really hearings, they are a tightly choreographed masquerade where the fix is in and the vast majority of parole candidates have no chance of making parole, no matter how low their risk assessment score, how much time they’ve served or what is presented at the hearing.

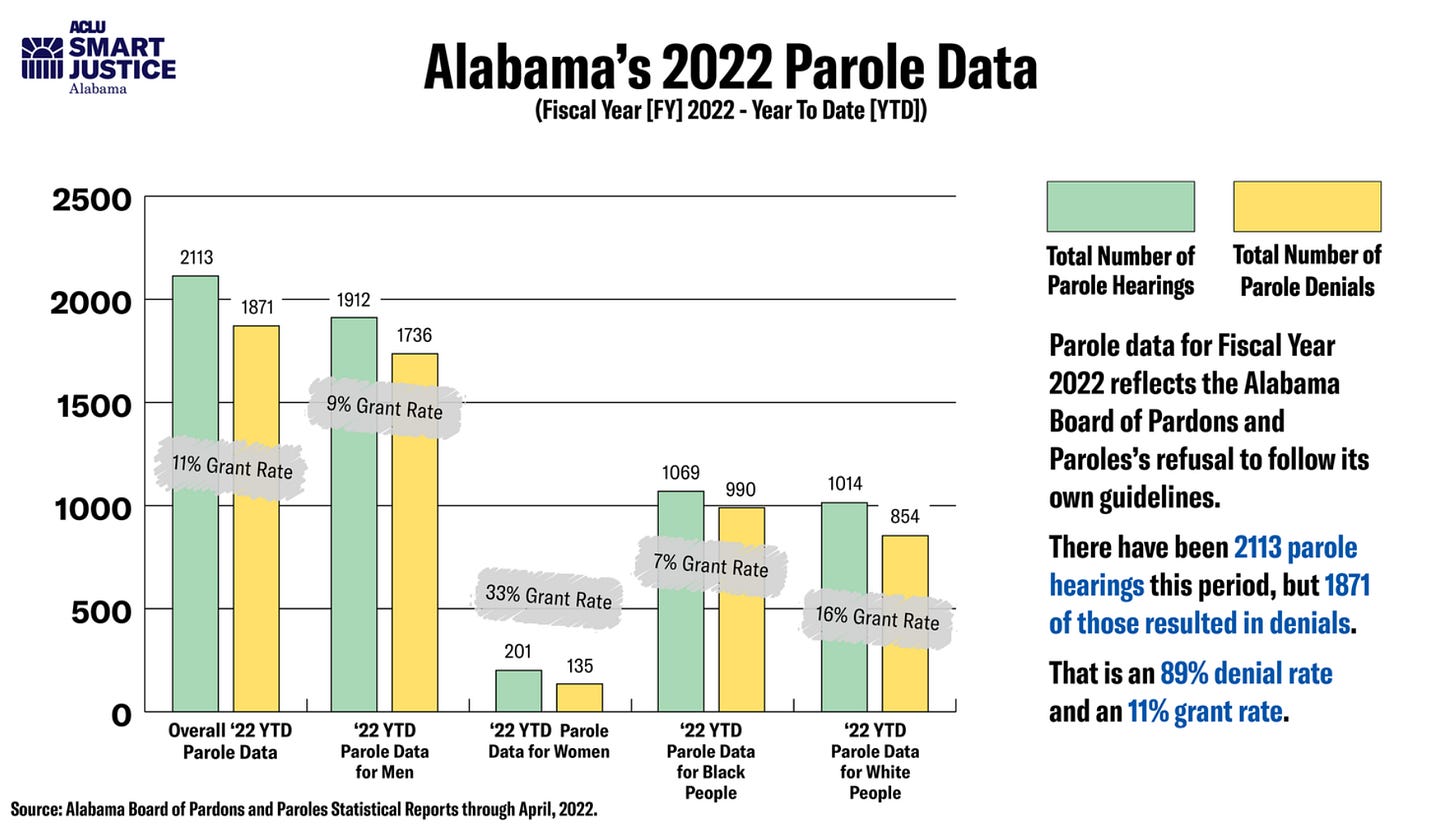

I recently reported on the abysmal parole hearing outcomes, especially for Black candidates (see above graphic), and the many ways all candidates are disadvantaged by the system itself, which is openly hostile to parole and contains almost no infrastructure to support parole advocacy, but bends over backwards to accommodate those who are categorically against parole, like Attorney General Steve Marshall and the crime victims advocacy group called VOCAL.

If you want to watch a video of parole hearings I produced, click here. It highlights the many disadvantages parole candidates face—that they aren’t even allowed to attend their own hearings, that there is no state-funded organization or office that supports parole, so they must rely on family or friends to travel to Montgomery and advocate on their behalf. And all 3 members of the parole board have backgrounds in law enforcement, so…. there’s that.

During the actual hearings, advocates who serve as witnesses are given three minutes to state why their person should be paroled, which in Alabama prisons is a matter of life and death. Then they sit down and listen to the other side rehash the crime, speak about their person in abstract and always urge the board to deny parole and set the next hearing for the maximum amount of time. In the vast majority of cases, the board votes in lockstep with recommendations from the AG’s office and VOCAL.

I watched this happen on April 13, when I sat through an entire docket. It was a depressing spectacle to watch, but what stood out most is how adversarial the entire process feels, with a total lack of opportunity for restorative justice. I don’t believe this serves victims. It’s sad the only option they are given is to relive their trauma by testifying in front of the parole board. And those who are advocating for parole have to sit across the aisle in shame. How does this help anyone heal?

The case I highlighted in the video was that of Jeffery Brian Parker, a 42-year old man who was convicted in a drug-related murder when he was 17. He’d been considered for parole 4 previous times, but each time he was denied after the victim’s family testified in opposition to his parole. Witnesses for Parker—his mother, his attorney and Albert Pugh, who runs a re-entry program and served time with Parker in prison, all told the board about his many accomplishments in prison, and asked them to look beyond his crime. Parker has a stellar prison record and has spent more time locked up than he did as a free man.

When it came time for the other side, the widow of the victim asked the board to deny parole, because she didn’t think 25 years was enough time. The AG’s office and VOCAL said the same, never referring to Parker (or any candidate) by name, only as “this inmate.” The representative from VOCAL told the board that Parker had accepted a plea deal, something that was settled by the court decades ago but was presented like a strike against him.

“He’s gotta serve. He had a capital murder charge, he pled down to murder,” said VOCAL advocate Doris Hancock. “It was originally capital murder.”

Parker accepted a sentence of life with the possibility of parole, but when it comes to people convicted of violent crimes, this board has taken that opportunity away. Only a handful of people with violent offenses have been granted parole under this board, all of them that I’ve been able to identify were serving time for robbery.

I recently requested a list of everyone granted parole serving time for a Class A offense, but a spokesperson referred me to the parole results on their website, which doesn’t include the person’s offense. I think they don’t want to draw attention to the truth that this board is categorically denying parole based exclusively on a person’s offense, even when their records, time served and risk assessment indicate they should be paroled.

At Parker’s hearing, the AG’s office made it sound like denying him parole was in keeping with his sentence, when the opposite is true. “We ask that you hold this inmate to the agreement he made with the court,” testified Sarah Greene, a victim’s service officer with the Attorney General’s office. “Please deny him for the maximum amount of five years.” And of course, that’s exactly what the board did, voting unanimously to deny him parole and set his next eligibility date for 2027 when he’ll be approaching 50.

Parker’s sentence is not life without parole, but it might as well be. He has done all the things the system has asked of him, despite the overcrowding, violence and deprivation, but it is never enough. When it comes to the sentence of life with parole, our sentencing law says a person is parole eligible after 15 years, but the punishment bureaucracy is against parole forever. They want life to mean death in prison and right now, it does.

“We thought he’d be out by now,” Parker’s father told me. “He trusted the justice system that he’d be out.”

Parker is in good company. Parole grants have gone from a high of 54% in 2017 to a new low of just 12% in 2022. That means 88% of people eligible for parole are being told they deserve to stay inside Alabama’s violent, overcrowded prisons. This is not in response to a spike in public safety threats. The trend was ushered in by the appointment of Leigh Gwathney in 2019 after a man on parole was arrested in the murders of three people.

The Jimmy Spencer case was a horrific tragedy, but one that points toward a failure of supervision by parole officers and actual correction by the Alabama Department of Corrections. Instead, Governor Ivey and Marshall blamed the parole board for releasing Spencer, but what they were really itching to end was the growing grant rates under a board utilizing risk assessments and an evidence-based approach in their decision making.

The shutdown of paroles was a typical reactionary response of punishing everyone for the actions of one. Similar events have occurred in other states—in 2010 the entire parole board in Massachusetts resigned after a parolee was arrested for killing a police officer. In 2013, parole grants in Colorado plummeted after a parolee was suspected of killing the state’s prison chief. And it’s happened in Alabama before too. In 1986 a parolee was arrested in a double murder and VOCAL applied political pressure to slash paroles for everyone. History repeats itself: the articles from 30 years ago reflect the same hopelessness unfolding in ADOC today.

Parole boards are in the business of risk, and there is always a risk someone will reoffend. Because of this, they tend to be risk averse, especially when they’re politically appointed. A national parole expert told me what should happen when someone on parole reoffends in a sentinel event (like the Spencer murders) is a holistic review of all systems that potentially failed. States should have a mechanism in place, he said, where multiple agencies examine what happened and take constructive, non-political steps to implement changes. “Imagine what would happen if reform was a broad effort, instead of a Governor and AG moving in to topple the existing system,” he said.

The parole board is running a show like some Soviet-era body that purports to give fair consideration to all cases, but follows marching orders to fix the outcomes a certain way, or else. Keeping the prisons as crowded as possible ensures the justification for Gov. Ivey’s $1.3 billion mega-prison scam. And these folks on the parole board make a nice salary: Gwathney’s pay in 2021 was over $100,000.

Alabama fancies itself as a state full of good people—Christian, Godly folks who go to church and claim that they read the Bible and strive to serve the Lord. But when it comes to compassion and empathy, many Alabamians reserve those for only certain people. Citizens who made mistakes and ended up in prison mostly get the middle finger from the free population, elected leaders and the parole board. Redemption has been cancelled when our system refuses to acknowledge that people change, that they can atone for their mistakes and are truly worthy of the second chances that the courts included in their sentences.

Sad situation indeed. I also attended a couple of hearings. At one of them, Ms Grantham of VOCAL, said the following about the inmate, "When he leaves prison, it should be in a pine box". Hate was dripping from her lips. I truly feel sorry for her to be living with such hate in her heart.

I find it extremely hypocritical that they refused to take the victim's family recommendation in the latest execution but they accept the victim's family recommendation when it comes to parole hearings. I thought prison was about rehabilitation. Evidently that is not the case in

Alabama.